(Unsplash/Priscilla Du Preez)

"Jessie, why can only men be real priests?"

Tess' question sent a golf ball-sized gulp down my throat.

A few months into my stint as a middle school youth minister, I was used to fielding tough questions from the pre-teen crowd: How do fax machines work? What does Incarnation mean? Can Jake really snuff out this candle with his fingers? Not being an expert in every eclectic discipline, I usually bumbled my way through a half-answer, suggestion, or in the latter case, an alternative idea to consider. I learned it didn't matter if I got every response exactly "right" — whatever "right" means. What mattered more to my youth was that I took their questions seriously and engaged them with honest effort.

Tess' question could be no different.

The Catholic Church tradition has maintained from the beginning that priestly ordination is reserved for men alone. Papal documents consistently cite three main reasons: Scripture says Jesus chose all men; the church practice has constantly imitated Christ in choosing only men; and the lived teaching authority of the church maintains that the exclusion of women from the priesthood is part of God's divine plan. I could have let these reasons be my sole response to Tess' question. The teaching after all "is to be definitively held by all the Church's faithful" in the words of Pope John Paul II. Lest anyone have any doubts, he reiterates, the issue is not up for debate.

Try leaving it at that with a 12-year-old girl — or a 28-year-old feminist theologian.

"I knew that just reciting a papal letter was not going to cut it. Doctrine without dialogue is deficient."

Standing in front of nearly 100 curious middle school students sprawled across the parish gym, I knew that just reciting a papal letter was not going to cut it. Doctrine without dialogue is deficient. I thanked Tess for her question and encouraged the group that questions are the key to unlocking new insights about faith. I flipped the table and asked Tess what the priesthood meant to her. After mentioning the three classic reasons for an all-male priesthood, I shared that I wrestle with this question too and named a few female saints that inspire me to keep going. I ended my response by affirming that God calls each and every person through baptism to do good work in the world.

For the next few days, I replayed the exchange in my head over and over. Did I do justice to Tess? To the church teaching? To the question itself? One aspect I did not question in the slightest was my decision to engage Tess's question. I know the church teaching. Twenty-one years of Catholic education, including the last three at a Catholic seminary, left me well-versed in Catholic code. I know the Vatican has tried for years to cut out any conversation that puts "women" and "priesthood" in the same sentence.

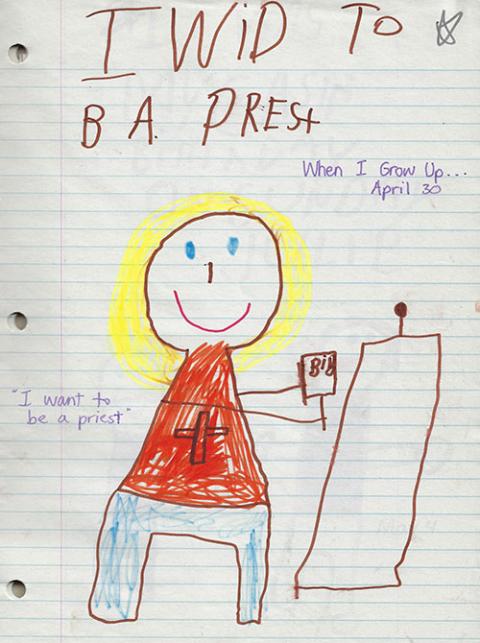

The author made this drawing when she was a child. At 5 years old, she was set to become a priest. (Provided photo)

The damage of dismissal

I also know the deep pain prompted when questions of calling are ignored. On kindergarten career day, while my sticky-fingered comrades scampered around the room fighting fake fires and trading princess tiaras, I scribbled a picture of a tall, lanky girl holding a cross and a candle. At 5 years old, I was set to become a priest. I wanted to talk about Jesus from the big stand up front. I wanted to sprinkle my friends with water and hand out the special bread and inspire people who lost hope. The career day question was posed again in fourth grade: what do you want to be when you grow up? My answer remained the same: I want to be a priest. From across the room, my teacher laughed. "Oh Jessie," she said, shaking her head. "You can't do that. Girls can't be priests in this church."

Dismissals damage, trust me.

Subtle and not-so-subtle messages from the Catholic Church rendered my call to priesthood empty or invisible for most of my life. Until graduate school, few engaged my calling. There are the fourth-grade teachers and conservative bloggers of the world who said explicitly no, you are wrong. Your call does not exist. But I've found the implicit messages more damaging. They formed me to dismiss my calling. Never seeing a woman near the altar told me I do not belong there. Never hearing God called "she" told me I am not made in the image of the divine, at least not to the extent of my male counterparts. Never speaking about women as pastoral leaders told me I do not have the authority to preside or preach or bless or baptize.

I know now that silence does not satisfy. It stunts.

We do our youth and adults a disservice by dismissing questions of calling. Instead, I believe we must create space for sharing. I want the Tesses — and Jessies — of the world to be encouraged to explore the depths of our callings and to dream big, whether those dreams end with collars around our necks or not. There is so much good, so much healing, that comes from speaking our truths and listening to the truths of others.

It makes sense for the church to ignite the sparks for such sacred conversations. Catholics are a people steeped in holy conversation. From Vatican councils to coffee hours, the people of God gather together to speak our truths. We speak in Scripture studies and on street corners. We speak during vespers and van rides. The Word became Flesh, giving the divine a human voice, human ears, and a human heart.

We speak like the one we seek.

Of course, dialogue between bumbling beings gets messy quickly. Questions around priesthood are complex, emotional ones. It pokes at the core of calling for some. It disrupts the status quo for others. Not engaging the question would be the easiest path — but easy is not the Christian way. Just ask the Word who suffered and died on the cross and then rose again. Molded in this image, we are a people who step into the mystery rather than away from it. We voice aloud the questions churning in our guts: My God, why have you abandoned me? Am I my brother's keeper? Who do you say that I am? Why can only men be real priests?

Advertisement

Dialogue vs. debate

Questions ignite the faith of believers then and now. The sparks of care and curiosity set afire the soul that seeks sanctity. It is my privileged responsibility as a minister to fan the flames of my fellow seekers, not extinguish them. Tess's question deserves dialogue because Tess is a human being with a dignity that Christian tradition demands be acknowledged. I cannot honor her dignity by ignoring her question. Those actions do not align. The doctrine deserves dialogue, too, if it is to truly serve as guideposts for living and not be relegated to just words on a page.

I want to underscore that I am calling for dialogue around Tess's question. Then-Pope John Paul II lamented the debates occurring on the subject of women and priesthood in his 1994 apostolic letter, Ordinatio Sacerdotalis ("On Reserving Priestly Ordination to Men Alone"). Toward the end of the letter, he writes, "Although the teaching that priestly ordination is to be reserved to men alone has been preserved by constant and universal Tradition of the Church and firmly taught by the Magisterium in its more recent documents, at the present time in some places it is nonetheless considered still open to debate."

This pope, just like those who held the chair of Peter before and after him, is concerned that people are trying to debate the legitimacy of the teaching. Indeed, there are many in this camp, Catholics who believe the teaching is unjust, disagree with its theological reasoning, or advocate for a more inclusive sacrament. I can understand why the pope, as one tasked with preserving church teaching, would feel threatened by such calls for change. But debates and dialogues are different.

A ciborium containing hosts and a flagon of wine are seen during Mass April 23, 2017, at St. Therese of Lisieux Church in Montauk, New York. (CNS/Gregory A. Shemitz, Long Island Catholic)

The goal of a debate is to defend an opinion and pick apart any argument to the contrary. Those on different sides of the debate issue are pitted against one another. Being right is more important than being in relationship. Feelings have no worth in a debate. This style of communicating is about finding flaws, not facilitating conversation. I agree with Pope John Paul II — opening up this sensitive issue for debate is not the way to start.

Dialogue, on the other hand, encourages people to grow in relationship with one another. We speak with instead of at during a dialogue. Questions arise like: Who is this other person speaking with me? What can I learn from their experiences? Do we have any shared experiences or points of agreement? Dialogues create space for a diversity of opinions. The goal of dialogue is to develop a deeper understanding of the feelings and thoughts of a fellow human being — and likely oneself in the process. What better way to honor the dignity of another than by engaging in an honest dialogue with them?

Again, I am not focusing here on the debate over whether or not women should be ordained. Instead I'm promoting dialogue on a real vocational question. I want pastoral ministers, parents, and teachers to be equipped with creative ideas for responding to the question that inevitably gets asked in one form or another during every unit on sacraments — who can be a priest and why?

While it makes sense for them to be part of the response, the three main doctrinal reasons for an exclusively male priesthood do not have to be the only answers offered. Imagine a space where we could explore the many dimensions of priesthood. Imagine a space where we could dive into the diverse images of the God who calls us all. Imagine a space where we could celebrate God's callings of women as women. Imagine a space where we affirmed the call of all the baptized to be sacramental ministers — and prophetic ones at that. Imagine the ways this dialogue could enliven the church young and old.

Pope John Paul II says it perfectly: this issue is a "matter of great importance." Like other matters of great importance — life, death, resurrection, for instance — dialogue about vocation and calling fans the flames of faith in those seeking truth.

Imagine what will happen when we let the sparks fly.

[Jessie Bazan is the editor and co-author of Dear Joan Chittister: Conversations with Women in the Church.]