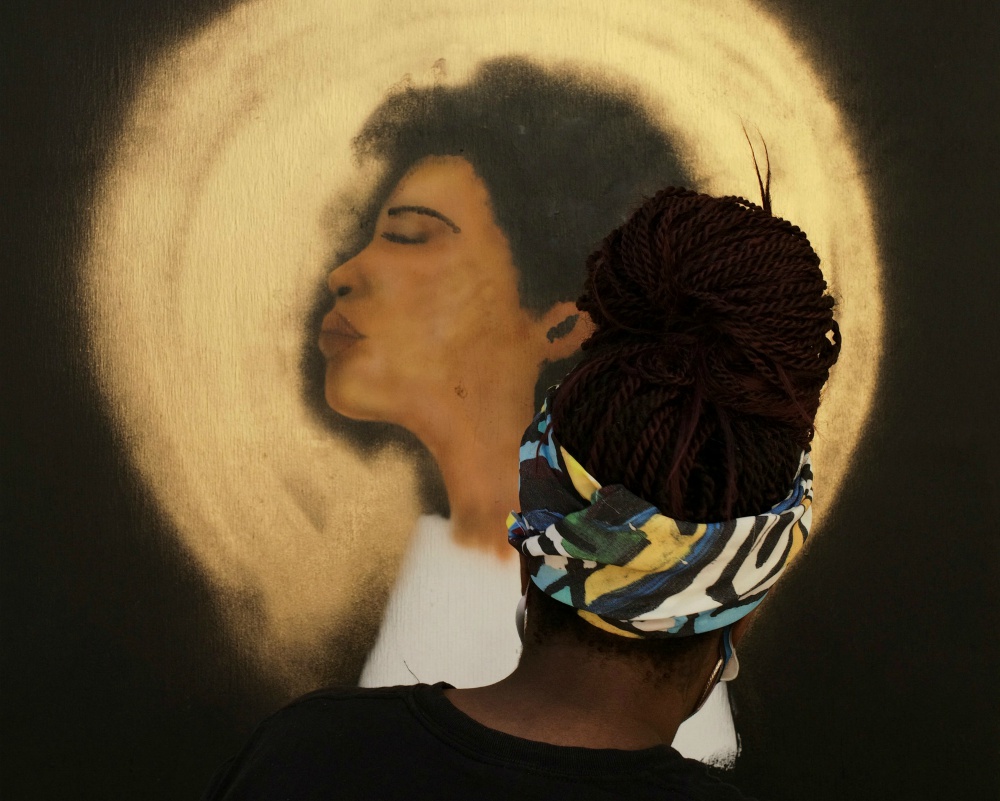

A woman in Washington paints a mural on the boarded-up windows of St. John's Episcopal Church at Black Lives Matter Plaza Sept. 5. (CNS/Reuters/Cheriss May)

On Sept. 23, a grand jury decided not to indict the officers involved in the March shooting death of Breonna Taylor, a 26-year-old Black woman shot and killed by Louisville, Kentucky, cops as she slept in her home.

Taylor is one of more than 800 deaths at the hands of American police officers in 2020, according to an online project that maps police violence.

Since her death in March, anti-racism protests have erupted across the country. A report released by ProPublica in July investigated hundreds of videos of police misconduct at many of these protests and found that in at least 184 of the videos, law enforcement used many tactics incorrectly.

"In 59 videos, pepper spray and tear gas were used improperly; in a dozen others, officers used batons to strike noncombative demonstrators; and in 87 videos, officers punched, pushed and kicked retreating protesters, including a few instances in which they used an arm or knee to exert pressure on a protester's neck," the report said.

According to a Human Rights Watch report released on Sept. 30, the New York Police Department, the largest police force in the country, violated the rights of hundreds of protesters at a June march in the Bronx.

A day before the Taylor verdict was announced, Los Angeles Auxiliary Bishop Robert Barron wrote, without explicitly naming organizers or groups, "One of the most remarkable differences between the social protests of the 1960s and those of today is that the former were done in concert with, and often under the explicit leadership of, religious people." The disconnect between religious people and those in racial justice movements, he insists, can be repaired through bridge-building.

Barron adds, "It is exceptionally difficult for the religiously motivated to get any traction with those formed by postmodernism, and vice versa. The two groups tend to stare at one another across an intellectual abyss."

Religious leaders can help organizers, he concludes, by helping them to reject the "nasty strain" of postmodernism behind "opposition leadership."

Barron's words do not exist in a vacuum; at any other moment in American history, this rhetoric from a bishop could be seen as merely laughable or tone deaf, but in 2020, it is dangerous.

Footage of armed militia floods our social timelines, as the threat of right-wing extremist violence grows. During the first presidential debate, President Donald Trump encouraged the members of an armed fascist organization to "stand by."

His sentiments are not surprising because we have already seen such rhetoric — more insidiously violent than the president's tactics but violent, nonetheless — from white men in our church this year. Thomas Daly, the bishop of Spokane, Washington, described members of BLM as "in conflict with Church teaching"; a priest in Indiana described BLM activists as "wolves in wolves clothing, masked thieves and bandits, seeking only to devour the life of the poor and profit from the fear of others," adding that the organization is "feeding off the isolation of addiction and broken families, and offering to replace any current frustration and anxiety with more misery and greater resentment."

Advertisement

I have previously written on the suspicion from our Catholic leaders toward racial justice efforts led by Black women, suspicion rooted in anti-Black misogyny, or what the Black, queer feminist scholar Moya Bailey describes as misogynoir.

I see this rhetoric from our church leaders, and I, like other women in our church, am on the receiving end of Catholic misogyny often. At least once a month, I receive emails or Twitter messages from white men who adopt the same patronizing tone used by men like Barron.

Men have offered to "educate me" about "reverse racism" in the church; some have told me all racial justice movements in the United States are "violent" and "supportive of terrorists"; others have shared links to what they view as the most "unchristian, anti-life aspects of BLM, including its promotion of dismantling capitalism and family life."

It is not just our president who can fuel racial hate.

There is an abyss in our church, and it is because the bishops, collectively, and, by extension, other leaders in the church are not listening to the true needs and desires of marginalized communities. A bridge is needed, as Barron said, but it is for the Catholic Church, where a true, Christ-centered love of justice is missing, a community led by men who often form incorrect opinions rooted in misogyny and who seem to ignore the cries of the Black faithful.

Anti-black misogyny has existed in our church and nation since the days of enslavement. To eradicate this system, our bishops must authentically and collectively engage with and accompany movements that are challenging Catholics to envision a faith centered outside of whiteness.

It is organizers, from groups like Black Lives Matter, the Dream Defenders, the Sunrise Movement and Black Youth Project 100 — many founded and/or led by citizens from marginalized communities — who are inspiring citizens to fight toward dismantling oppressive systems, fighting for Black life and dignity, and standing in solidarity with one another.

Until we do so, our church leaders will continue to provide a disservice to the faithful who are struggling to understand what role their faith plays in the movement for Black lives.

I'd like to conclude by offering some fraternal correction, which Barron described last month as "the traditional term for constructive criticism of our brothers and sisters." In 2015, Opal Tometi tweeted, "I'm a Christian." Tometi, one of the founders of the Black Lives Matter movement, credits Catholic philosophies like liberation theology with her commitment to fighting for the most marginalized, including her work focused on helping African immigrants.

Those marching in the streets are teaching us the true meaning of Catholic justice, one centered on, as Pope Francis describes in Fratelli Tutti," a "love of justice itself, out of respect for the victims, as a means of preventing new crimes and protecting the common good, not as an alleged outlet for personal anger."

White bishops just need to humble themselves and walk that bridge. As we head into an election, that means bishops explicitly and collectively rejecting anti-Black, misogynistic language and actions.

[Olga Segura is NCR opinion editor. Her email address is osegura@ncronline.org.]