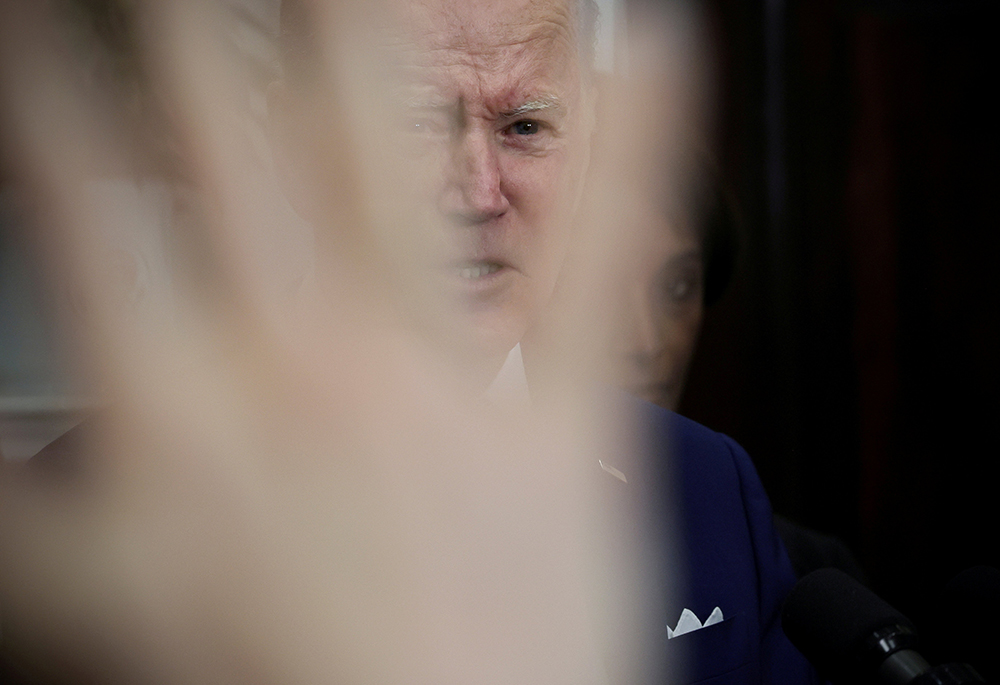

President Joe Biden takes questions from reporters at the White House May 4 in Washington, after delivering remarks on economic growth, jobs, and deficit reduction. (CNS/Reuters/Evelyn Hockstein)

The nightly news leads with stories about gun violence, protests against the Supreme Court's anticipated overturning of Roe v. Wade, and gay pride celebrations. But polls indicate that Americans' top concerns are not these hot-button social issues but kitchen table economic issues like inflation and gas prices.

An ABC/Ipsos poll last week found 83% of Americans naming the economy as a major consideration in how they will vote come November. Eighty percent named inflation as a major concern and 74% cited gas prices. President Joe Biden's poll numbers on all three are dismal. "Only 37% approve of Biden's handling of the economic recovery, and even fewer approve of his handling of inflation (28%) and gas prices (27%)," the ABC report said.

The irony is that there is very little this president — or any president — can do about macroeconomic issues like inflation and gas prices, which are tied to world markets.

The president's failure to get his "Build Back Better" agenda through Congress haunts him not because it would have affected inflation or gas prices in the short term, although some of its climate change provisions would have insulated us from volatile fossil fuel markets by making us less dependent on those fossil fuels. It is the inability to lower prescription drug prices, the cost of child care or reinstate the child tax credit that hurt voting Americans. A recent report from the Lending Club indicated that 61% of Americans report living paycheck to paycheck. It is an astonishingly high number. That is the number the White House should fear.

Americans also register strong concerns about gun violence, with 72% saying the issue is "extremely" or "very important" in deciding how to vote, and another 63% cited abortion. But, people on both sides of the abortion issue may cite it as a major concern, and the same with gun control or LGBT rights. There is academic literature offering all manner of interpretation about why people vote the way they do, but the dirty secret about American politics is that voters decide elections based largely on the state of the economy, while campaigns are largely funded by special interest groups that demand relatively extreme policies on social issues if their party wins. That steady stream of funding guarantees the culture wars will continue.

At the Texas Politics Project, Jim Henson illustrated the way extreme positions on gun rights have failed to cost Republicans control of that state's government. In the wake of the massacre in Uvalde, he wrote:

In stark political terms, despite the evidence of broad public support in Texas for measures like background checks and (to a lesser extent) red flag laws, Republican voters have rewarded Texas Republicans for moving in the opposite direction, and elected officials are likely counting on them to reward them again for preserving the status quo when it comes to measures directly related to gun access and ownership.

In blue states, it is the abortion rights lobby, not the Second Amendment lobby, that rewards extreme positions with campaign cash.

For most Americans, economic issues do not require moral analysis, which is reserved for social issues. This reverses the relationship of political legitimacy and moral probity the Puritans conceptualized. As Cathleen Kaveny observed in her book Prophecy Without Contempt:

For the Puritans, the breach of the covenant was their prevailing sins, which were more or less uncontroversial; the penalty was the loss of material prosperity. In our era, however, it seems that this structure is completely reversed. The uncontroversial covenantal obligation is to secure the nation's economic and military well-being. Political parties that do so are rewarded with the opportunity to implement their own, contested vision of what counts as virtue and vice.

I have my reservations about the extreme providentialist worldview that animated the Puritans, to be sure, and they had their own kind of culture wars in the 17th and 18th century. But reversing the source of covenantal obligation doesn't point to a better politics either.

Enter Catholic social doctrine. Catholic teaching does not arrogantly argue high gas prices are necessary medicine in the fight against climate change, dismissing the day-to-day concerns of voting Americans as did this column by Jon Talton in The Seattle Times. Telling voters who are struggling to make ends meet that their concerns are benighted is never a smart political strategy.

Advertisement

Instead, Catholic social doctrine places economic concerns in a proper perspective: Is the economy structured such that it respects the human dignity of all while serving the common good? In the case of gas prices, struggling workers should not be expected to feel good about what they pay at the pump because it will help with climate change. The society should invest in electric cars and other sustainable energy changes so that the working poor, who struggle enough, do not bear an unfair burden.

Catholic social doctrine does not dismiss social issues nor value them more than economic ones. Instead, it assesses both economic and social issues through the same moral lens: Do liberal abortion laws really empower the poor? Does our society reward companies that serve the common good by allowing workers to unionize, and if not, why not? Respecting the human dignity of LGBT employees demands extending legal protections to them in the workplace, but how to balance that with the religious liberty, which also serves human dignity, of a church or ministry? Do our tax policies give outsized benefits to fossil fuel corporations with billions of dollars in profits? Why were Democrats so keen to remove the cap on the deductibility of state and local taxes, which would only benefit the affluent?

The four pillars of Catholic social doctrine — the common good, the inviolable dignity of the human person, solidarity and subsidiarity — can be applied to all issues. The Holy Father's insight in his 2015 encyclical Laudato Si' and, even more in his 2020 encyclical Fratelli Tutti — that all issues are actually interrelated, that there is an integral quality to human development — demands that we not set aside our moral compass when we turn to one or the other sets of contemporary political concerns.

The libertarianism that is so strong in the American political psyche remains what Pope Pius XI said it was, a "poisoned spring," from which all manner of social ills flow. Catholic social doctrine is the antidote. It is a font that never dries up. Too bad it fails to register in the political attitudes of most Catholics, let alone most Americans.