An image depicts burning royal carriages at the Chateau d'Eu during the French Revolution, c. 1848. (Library of Congress/N. Currier)

John McGreevy's new book Catholicism: A Global History from the French Revolution to Pope Francis is, as the title suggests, ambitious. Even at a little over 400 pages, how to distill a "global" history over such momentous centuries? And to do so at a time when most academic research is increasingly specialized and narrowly focused?

McGreevy, who is the provost at the University of Notre Dame, somehow manages to pull it off. The skill needed here is not so much editorial, although the ability to condense complicated events and arguments into concise prose helps enormously. No, the most essential skill to achieve a balanced, thoughtful and readable history such as this is judiciousness, the ability to assign the proper values to the different events and people being surveyed, weighing each in terms of its significance to the arc of the story as a whole.

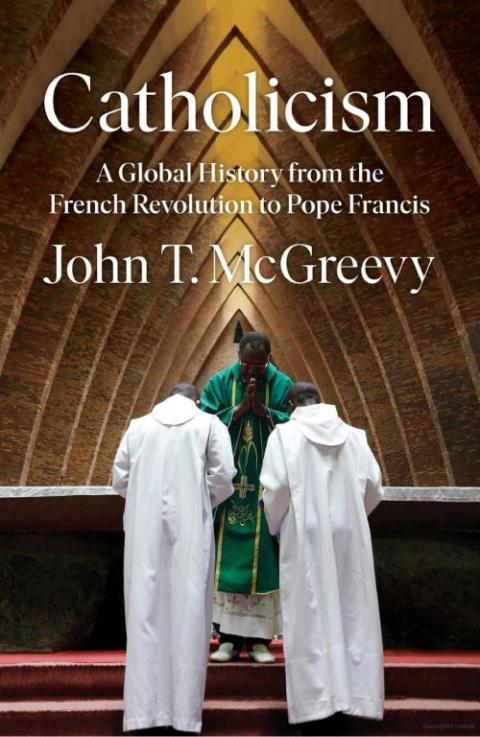

"Catholicism: A Global History from the French Revolution to Pope Francis" by John T. McGreevy

We live in an era that is ideological in tone and temperament, as are the centuries surveyed in this book, and the writing of history has not been spared by this reality. But history is the enemy of ideology. It complicates narratives and uncovers exceptions to dominant themes. Facticity resists the kind of monocausal explanations that make paradigms possible. History keeps us, or should keep us, from superimposing the attitudes of the 19th century back onto the 18th century or conflating attitudes common in a Protestant milieu like the United States with attitudes found in a Catholic one. From all these historiographical sins, McGreevy’s volume is splendidly and mercifully free.

The opening chapters detail not only the major themes that characterized the French Revolution (and the philosophic and cultural maelstrom that preceded and accompanied it) but show how some of them found a sympathetic hearing in certain Catholic circles. Only in later times did Catholics come to view the French Revolution as a total disaster and condemn any ideas associated with it. At the time, there were Catholics, and even clerics, who supported the rights of a national church against papal encroachments, who backed the suppression of the Society of Jesus because of its ultramontanism, who suppressed the devotion to the Sacred Heart of Jesus that the Jesuits promoted, etc. Disentangling these themes and the characters who held them, and setting all in the context of the march of fast-moving events, is one of McGreevy's achievements.

Here, too, I would register one of the few omissions that rises to the level of a complaint. In looking at the career of John Carroll, the first bishop in the United States, McGreevy places him among those who embraced a kind of Catholic Enlightenment. Carroll "had requested an English acquaintance to send him writing on the limits of papal authority and the desirability of the liturgy in the vernacular," McGreevy writes. "For a time, John Carroll favored priests electing their bishops as recommended at the Synod of Pistoia." All true.

John T. McGreevy, provost at the University of Notre Dame, is the author of "Catholicism: A Global History from the French Revolution to Pope Francis." (Matt Cashore)

McGreevy is not alone in this characterization of the first bishop in the U.S. Such esteemed church historians as Joseph Chinnici, Jay Dolan and James Hennessey have all made similar arguments that Carroll was sympathetic with the Catholic Enlightenment. I have long been persuaded by the counterarguments of the late Jesuit historian Charles Edwards O'Neill, who detailed the many ways Carroll exhibited precisely the attitudes the Catholic Enlightenment abhorred. You can pick which side you think has the better argument. But McGreevy should have noted that Carroll was a Jesuit, so there were clear limits to his sympathies with Catholic reformers!

The period from the close of the revolutionary era with the defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo in 1815 to the revolutions of 1848, which pushed the papacy squarely into the reactionary camp, is one of the most interesting in Catholic history, but also one of the least studied, at least in this country. Important thinkers like Charles Forbes René de Montalembert and Félicité de Lammenais, two leaders of liberal Catholicism in this era, come alive in McGreevy's telling, complicating the dominant narrative of an increasingly conservative and ultramontane church.

Similarly, McGreevy's treatment of Jacques Maritain will acquaint a new generation of readers with the man who, more than any other, revivified Catholic political thought in the mid-20th century and laid the groundwork for what remains the political order most consistent with Catholic social doctrine, the Christian democracies of postwar Europe.

It is not just people who benefit from McGreevy's treatment. Broad sociological facts like colonialism and decolonization are ably treated, with the broad picture emerging but never in ways that blot out particularities that complicate or refine that picture. For example, McGreevy not only introduces key advocates for indigenous clergy and accommodation to local culture in colonial-era Catholicism, evangelists such as Vincent Lebbe and Ma Xiangbo, but also how the papacy came to align itself with this desire to build up an indigenous church even in the face of criticism and hostility from the colonial powers.

Advertisement

When McGreevy gets to Vatican II, his skills as a chronicler shine. In detailing the post-war, pre-conciliar challenges that made the calling of a council necessary, he writes:

Another unexpected challenge was prosperity. The economic boom in Western Europe and North America after World War II pulled millions of Catholics, as much or more than any other group, into the middle class. Income levels for Catholics in both West Germany and the United States reached or exceeded national averages for the first time in the early 1960s. One Jesuit sociologist wondered if "group solidarity" might wither. "It is not so much that religion and moral law are denied or rejected," he wrote, "[but that] they are simply judged not pertinent as guiding norms of practical action."

Alas, some of our conservative friends, even with the benefit of hindsight, still fail to see this reality.

And, on the very next page, describing the clerics, and they were all clerics, chosen to prepare draft texts for the council, McGreevy shares a quote from Henri de Lubac that I had never heard before. The clerics in the curia who penned the drafts inhabited "a small academic system, ultra-intellectualist without being intellectual." Ouch.

If I had been McGreevy's editor, I would have suggested concluding this volume with the close of Vatican II, or at least with the immediate post-conciliar developments such as the emergence of liberation theology and Rome's crackdown against it. Instead, the final chapter is on the sex abuse crisis, and that strikes me as still a subject for journalists. Journalists get to write the first draft of history, not the last, and the reverse is also true.

Historians need to have the papers of Pope John Paul II and the correspondence of key figures in the hierarchy before a history of the crisis can be adequately written and key features, opaque at the moment, can emerge. History is cold-blooded and it is distance that allows the blood to cool.

Such quibbles are small beer in a book with 66 pages of footnotes! This is an excellent book that thoroughly lives up to its ambitions. Given the hyper-specialization of so much academic history these days, the accomplishment here is even more notable: a readable, thorough and judicious treatment of a global institution over more than two centuries. If you are a bishop thinking of what present to make to his clergy at Yuletide, or a Catholic school principal thinking the same for her faculty, you could do much worse than give them a copy of this fine book.