A man is pictured standing on a roof behind a barbed wire fence at the Otay Mesa Detention Center for those entering the U.S. illegally seeking asylum in San Diego July 2, 2019. (CNS/David Maung)

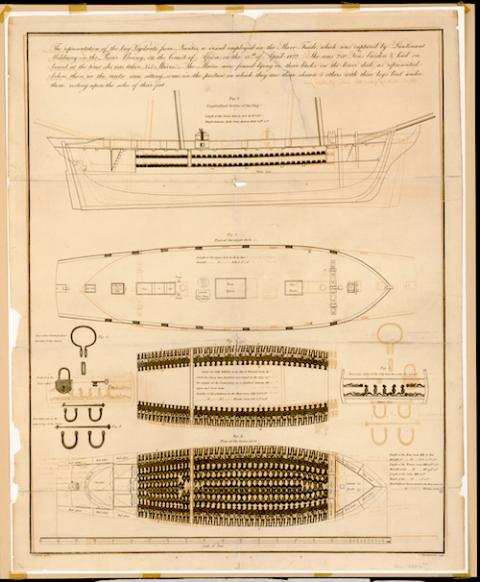

During my city's virtual ceremonies commemorating Juneteenth, poet Terry E. Carter shared his poem "Slave Ship Soliloquy." The poem draws a picture of what the Middle Passage was like, and the ways we are currently living in the shadows of that most horrible design. Twelve million men, women and children were stolen and transported across the Atlantic. Two million didn't make it, perished or were killed, dumped into a watery grave. Carter made a point to include the plans of ships used during the slave trade as a backdrop for his poetry reading, designs for mass dehumanization. This evidence demonstrates how the human race is adept at shackling and containing the bodies of those it seeks to present to the world as less than human.

Engraving by J. Hawksworth of S. Croad's representation of the slave ship Vigilante, from Nantes, captured by Lt. Mildmay in Bonny River on the African coast, April 15, 1822, while it was carrying 345 enslaved people (Library of Congress)

For the past six years, U.S. residents have been challenged by the design of migrant detention centers. Many of these continue to serve the purpose of holding thousands of minors and children separated from their families at the border. Two years ago, various architecture and design organizations considered the question of whether it was ethical to design these detention centers. At the heart of this question was whether they could use their talent to improve conditions for human beings who would be detained. Would they be able to design more humane holding cells? Would that laudable goal be worth their collaboration with an industry focused on detaining human beings, sometimes indefinitely? Their reflection led them to a resounding "no!"

On June 20, 2018, The Architecture Lobby (T-A-L) and the Architects/Designers/Planners for Social Responsibility (ADPSR) issued a joint statement on immigration enforcement and the complicity of their professions:

For too long, architects have been complicit in human caging by designing and building these structures. Architects designed the facilities where children call out for their parents at night. Architects also designed the extensive network of facilities where their parents shiver in frigid holding cells. History has taught us that what is strictly legal is not always what is just. It is time for this to end. We call on professionals to join us in this pledge: We will not design cages for people.

Who are the builders and designers of architectures of hate? We insist that we could never be part of building infrastructure for the mass transport of Jews to concentration and death camps, or constructing barracks for holding Japanese and Japanese Americans in internment camps in the U.S. And we certainly don't see ourselves as ever designing ships for trafficking human beings during the trans-Atlantic slave trade. We like to cleanse our industries, freeing our day-to-day business from the kind of harsh moral evaluation reserved for extreme cases. The grave sins of planning and building infrastructures of hate do not enter into our considerations about the common good, of our jobs, education of our children, investments of our retirement accounts and the development of the technologies and systems that make our lives run with ease.

Advertisement

Certainly the Catholic moral tradition has resources to place our daily activities within a matrix of social responsibility. We can be directly morally culpable for evil, but this is a rarity. More often than not we are trying to discern the degrees of our cooperation, especially when considering such issues of the common good as voting for a candidate that might not have a consistently pro-life position. We also would do well to ask questions about the "appropriation of evil" whereby we benefit from the product of practices that do harm in ways far removed from us, such as consuming technologies that depend on forced or slave labor.

The current protests in the U.S. over violence against Black and Brown folks by police highlight the ways in which some forms of social architecture serve the purpose of restraining and containing human bodies. The police force, criminal justice system, and the prison and migrant detention industrial complexes are part of our social architecture. And like the architectures that structurally supported such evils as chattel slavery and Nazism, their functioning depends on many people not questioning their moral culpability in everyday life. We wash our hands of the evil of building and perpetuating structures that work to contain and abuse the bodies and lives of those considered less than human, undesirable by the establishment and defenseless before our indifference.

Gang members are seen in a photo released April 25, 2020, being secured during a police operation at Izalco prison in El Salvador during the COVID-19 pandemic. (CNS/Reuters/El Salvador Presidency handout)

In late April, haunting images of inmates at the Salvadoran Izalco jail caught my attention. They, too, depicted the craft of an architecture of hate put at the service of controlling the bodies of those deemed undesirable. The particular positioning of the inmates' bodies, in long rows, sitting astride, back to stomach with hands tied, has long been a design for controlling against riots or revolts, visible as well in some of the designs for transporting African persons stolen for the slave trade. The response to the COVID-19 epidemic by the right-wing Salvadoran government of Nayib Bukele has come under scrutiny for its gross violations of human rights. This is most visible among the poor in El Salvador. When left unchecked, the drive to shape the common good for only a few or only those with resources and power results in the repeated violation of the human soul through the careful construction of architectures of hate.

The current moment of protest and pandemic provides an opportunity for a critical examination of our public and personal consciences with respect to the various architectures of hate, social and physical, that we uphold by our participation, directly or indirectly. Building for human dignity requires recognizing how sin injects itself in every age into our day-to-day efforts at designing the common good.

Rather than respond to calls to "Defund the Police" with skepticism and derision, could we join discussions examining how city budgets and resource allocation are a form of social architecture that ought to uphold the good of every member of the community? Rather than see Black Lives Matter protests as chaotic interruptions of the everyday, can we hear in them a call to a national act of contrition, an obligation to examine our participation in architectures of hate and in turn work to dismantle them?

[María Teresa (MT) Dávila is associate professor of Practice, Religious and Theological Studies at Merrimack College, North Andover, Massachusetts.]

Editor's note: We can send you an email alert every time a Theology en la Plaza column is posted to NCRonline.org. Go to this page and follow directions: Email alert sign-up.