People outside a Catholic church in a village in Malanje Province, Angola, in 2018 (Dreamstime/Nuno Almedia)

The southern African nation of Angola will hold elections later this year that could see the ruling Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola lose power for the first time in nearly five decades.

The August vote will come as the country, a former Portuguese colony, faces a serious crisis as it endures a fifth straight year of economic recession.

Although there is general dissatisfaction with the popular movement, known by the acronym MPLA, civic leaders, including a range of Catholic officials, have expressed concern that the vote could be manipulated to keep the ruling party in power.

In a Feb. 7 statement, the bishops' conference of Angola and São Tomé said that Angola is being impacted by "fearful poverty, loss of purchasing power, galloping unemployment, degradation of habits, empty dialogue between the parties and society, and high levels of intolerance."

The bishops also referred to the general belief that MPLA will not allow the elections to be properly monitored for their legitimacy. "Much reflection and dialogue are needed, and everything must be done so the parties do not assume more importance than the nation," said the bishops.

Advertisement

A few bishops have become more and more outspoken about the poor living conditions in Angola — and about MPLA's responsibility for them — over the past few years. Particularly since October 2021, when a new board was elected to direct the bishops' conference, the Angolan episcopate has taken a more prophetic voice regarding politics and social issues, which at times has displeased the authorities.

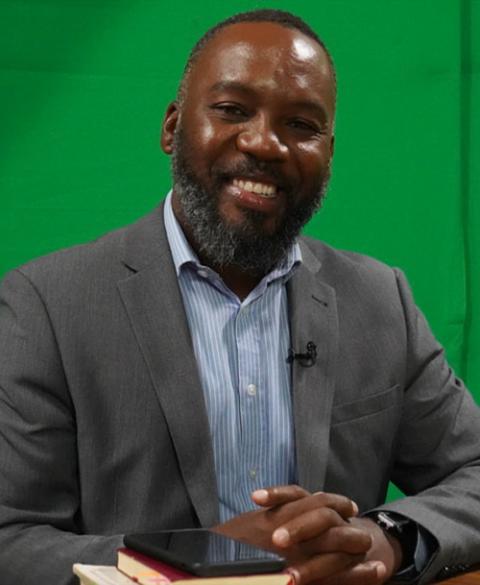

"Many bishops have been frankly criticizing the situation in the country, and the regime is not comfortable with it," Olívio N'Kilumbu, an Angolan political analyst and university professor, told NCR.

N'Kilumbu mentioned as some of the most fearless social critics: Saurimo Archbishop José Manuel Imbamba (the conference's president), Dundo Bishop Estanislau Chindecasse (the conference's vice president) and Caxito Bishop Mauricio Camuto (the conference's secretary general).

"They are relatively young bishops and have close contact with poor families and the youth. They know how the Angolans suffer," said N'Kilumbu, who teaches at Óscar Ribas University in the capital of Luanda.

Olívio N'Kilumbu, an Angolan political analyst and university professor (Courtesy of Olívio N'Kilumbu)

The Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola and its primary rival, the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA), were both originally organized as anti-colonial guerrilla movements during the Angolan war of independence (1961-74).

In 1975, MPLA, which was originally communist, assumed power after independence from Portugal, but a war against anti-communist UNITA persisted till 2002. Since the introduction of a multiparty system in 1992, UNITA became the major party of the opposition, but MPLA has kept power until now.

Analysts like N'Kilumbu argue that the younger generation of clergy members do not have a personal history of attachment to one side or the other, and thus tend to feel free to criticize politicians when they see fit.

"They are pastors and feel the need to accompany their flock during hard times. The church is present in zones where the state itself is absent. So, it wants to liberate the country from suffering," said Albino Pakisi, a former priest and a political commentator at Radio Ecclesia, a church-run radio station.

That sentiment echoes a growing feeling of rebellion among young people, especially the generation that was born after the war. While the general unemployment rate sits around 33%, nearly 60% of young people are unemployed.

"The youth suffer the effects of exclusion. But they are on social media and see how their generation is protesting all over the world. Political pressure comes from them, and I do not think they will retreat," said Fr. Jacinto Pio Wacussanga, a sociologist and leader of two nongovernmental organizations that have been outspoken about a hunger crisis in the south of Angola since 2012.

People are seen after Sunday Mass in Baía Farta in Angola's Benguela Province. (Dreamstime/Igor Kiporuk)

Wacussanga has been trying to assist hundreds of families who were impacted by a serious drought in the provinces of Huíla, Cunene and Namibe. He says he has alerted the national government on several occasions about the need for irrigation projects in the region, but nothing was done. Now, he has been demanding the distribution of food kits to the most affected.

"There are people literally starving to death, but nothing was done to help them. To make things worse, denialists in the government said that there is no hunger in Angola and blame the poor for their poverty," he told NCR.

Wacussanga and many in the church asked the government to declare a state of emergency in the region — which would allow Angola to receive international relief funds — but President João Lourenço has resisted the idea, fearing possible political consequences.

Franciscan Sr. Emiliana Bundo at a celebration of her 45th anniversary of consecrated life last year, with Archbishop Filomeno do Nascimento Vieira Dias of Luanda, Angola (Courtesy of Radio Ecclesia)

Sr. Emiliana Bundo, a member of a Portuguese Franciscan congregation who ministers to those in need throughout the capital, said she has urged the government to take more measures to increase domestic food production.

"Importing food will not solve the problem of hunger. People are starving both in the cities and in the countryside. Extreme poverty is gigantic," she told NCR.

More than half of Angolans live below the poverty line, and at least one-third face extreme poverty, according to the World Bank.

Pakisi, the former priest, said the ruling MPLA "had four decades to change that situation. But it prefers to give excuses."

"Before 2002, they claimed that all problems were the result of the civil war," he said. "Twenty years later, things are even worse."

Pakisi said most of the Angola's population of 31 million is tired of the same party and wants political change. He argued that the church cannot denounce misery and suffering without blaming the MPLA.

"The church's social doctrine establishes that any government should prioritize the poor. But the MPLA is corrupt and has only increased poverty," he said.

Bundo worries the elections may increase social tension and lead to conflicts.

"We need electoral transparency. If things are not carried out in a transparent way since the beginning, we will have problems," she claimed.

Albino Pakisi, a former priest and a political commentator at Radio Ecclesia, a church-run radio station in Angola (Courtesy of Albino Pakisi)

At least two petitions were created in 2021 by journalists, activists, priests and other members of civil society requesting an equitable and fair composition of the electoral commission and asking international observers to monitor the upcoming elections.

N'Kilumbu said the MPLA will have total control over the elections and that there will not be an adequate number of observers and monitors.

"The elections will not be transparent, free or fair," he said.

Pakisi agrees. He believes that MPLA will do all it can to hang on to power.

"They may arrest protesters, political commentators and even priests, depending on the situation. That is precisely what the bishops are trying to avoid by alerting the government now," he said.

Pakisi emphasized that there are pious Catholics in high governmental positions, and that the bishops' criticism is also a way of trying to raise awareness among them to avoid chaos.

The church's teaching role is also central in Angolan society as a whole, said N'Kilumbu.

"A recent survey showed that the Angolans have much more trust in the church than in the government. The church has a stabilizing role. That is why its voice is so important when it demands free elections," he said.

Catholics who work with the neediest in society, like Bundo, hope that despite all odds something can change in the near future.

"The people cannot deal with promises anymore. They want change," she said.