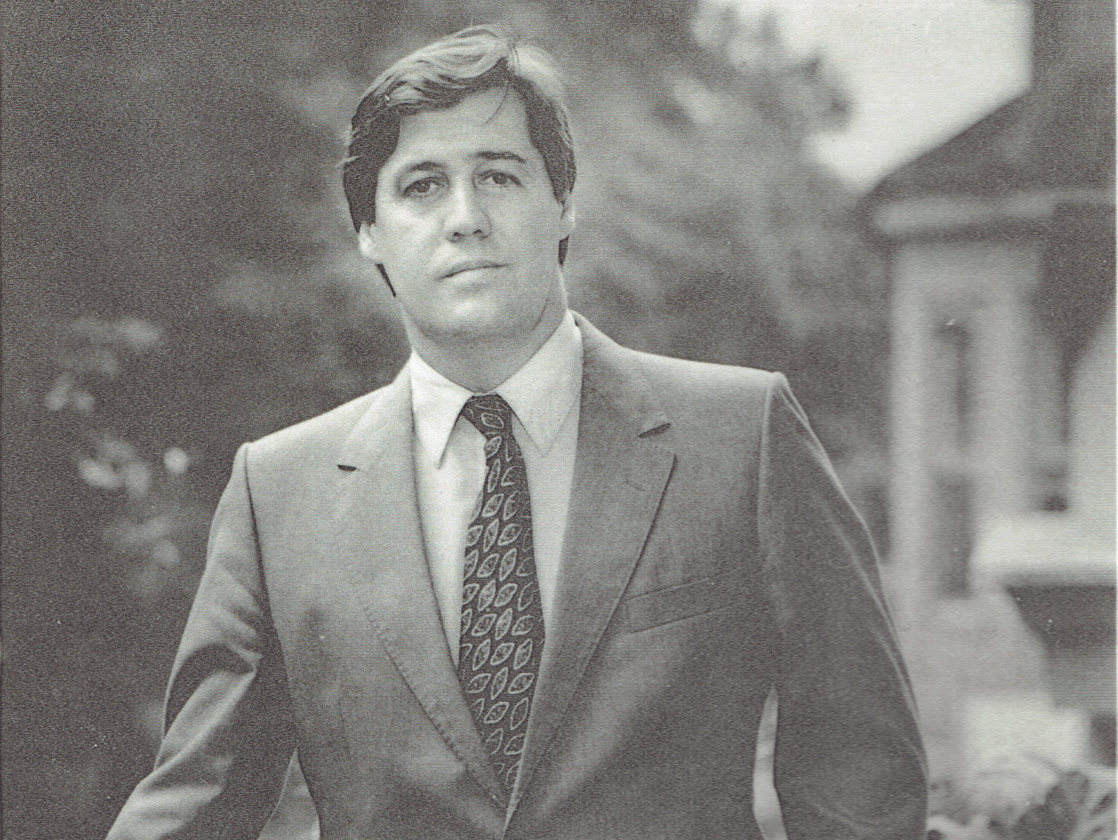

Jason Berry's portrait as it appeared in his 1992 book "Lead Us Not into Temptation." (Provided photo)

Jason Berry loves character-driven narrative. He's good at writing it, sending wonderfully drawn figures, whether wretches of the clerical sort or zany, colorful Louisianans, on journeys along a tight weave of data and history.

And himself? Berry, who recently turned 70, is a character who's bounced between those poles, the weave supporting him a mix of his intense examination of the ugliest side of Catholic reality and the soul-restoring gumbo of Louisiana life, particularly his hometown New Orleans.

NCR has run tens of thousands of Berry's words on our pages in the past three-plus decades, but we've never spoken to him or about him much in these spaces. This is a stab at doing that, a gathering up of conversations that have gone on for years and, more recently, during the months since the release of his latest work, City of a Million Dreams: A History of New Orleans at Year 300.

Full disclosure is warranted: Berry and I count each other as friends, meeting first as deliverer and recipient, respectively, of pitches for stories about the Catholic clergy sexual abuse scandal; then as writer and editor going round for round over the words, the data, the characters, the numbers; and spending hours on conference calls with lawyers vetting stories that delivered the details of ecclesial corruption — sexual and financial.

The cover of Berry's latest book

And beyond, as husbands, fathers and Catholics who by dint of profession had read more transcripts, communiques and depositions detailing ecclesial depravity and mendacity than most. We've spent more time than perhaps anyone should trying to figure out how such outspoken public moralists as the Catholic bishops had become symbols of the utterly immoral. How so many of the loudest, publicly self-proclaimed devout refused to believe any of it until the evidence overwhelmed.

I recall a conversation during the late 1990s or early 2000s — likely a discussion over yet another possible assignment having to do with the sex abuse crisis — when Berry announced in rather strident terms that his first love was not writing about the church's failures. "I'm a jazz writer!" he said.

Whether that was more unfulfilled wish than entirely true, I can't be sure. But in an appearance earlier this year at Politics and Prose, a landmark Washington, D.C., bookstore, he described toggling back and forth between church scandal stories and the jazz funerals that began to captivate him nearly 30 years ago. "What explains the ritual of jazz funerals was the question that started the research that resulted in" City of a Million Dreams, he told a crowd jammed into the back of the store.

He explained that historically the bands played dirge-like pieces heading into the cemetery but once "unto dust you return" was pronounced, the tunes went up tempo, into music that would give the impression of anything but sadness and death.

In the mid-1990s, the music and the movement of the second line, the troop of dancers that spontaneously gathers to follow the band, turned to something wilder and edgier. The performances began to reflect, Berry said, the mood surrounding the funerals of increasing numbers of young drug overdose victims. "Different cities tell their stories in different ways," he explained. He found the funerals for the victims "arresting" to witness, and he began interviewing older musicians who were upset "about the spirituality of the event being ripped out by the wildness of these funerals. That's what set me on the road that culminated in the book," he said.

"The story of my life since then has been a series of long intervals where I went off writing about the Catholic Church and the crisis which I chronicled for about 30 years," work that resulted in scores of articles and three books. Because of the years during which Berry was the principal — and often sole — chronicler of that crisis, he became its expert by default. But the New Orleans project kept pulling him back. When Berry cleared the decks for the final push on his latest book, he realized that after all of the interviewing and reading and research, he had come to the conclusion that "the story of the funerals began with the story of the city." The two stories were inseparable.

These twin forces, the cultures of Catholicism and New Orleans, have driven the main character in the Jason Berry narrative for the past few decades.

Early years

The seeds of fascination with the city in which he was born and the church in which he was raised were planted and nourished long before his own work — countless articles and a pile of books including a history, a novel, and several resulting from deep investigative reporting — began to pile up on his shelves.

Advertisement

His mother, Mary Frances, half Irish, traced her matrilineal heritage to Jalapa, Mexico. His father, Jason Sr., was raised in Arkansas. His parents, now deceased, met in New Orleans after World War II, during which his father had served in the military. His father was a business man, head of a cafeteria chain. His mother, who later in life was but a dissertation away from a doctorate in literature, was "really a radiant lady," and "probably the reason I became a writer." His childhood, he said, was "wonderful."

"When you are raised in a place where the adults wear masks and dance in the streets, it does promote a certain optimism for the human experiment. And I carried a certain joie de vivre, even through Jesuit high school, where I got the Irish church in full measure."

Berry also got a good dose of Jesuit social justice indoctrination, enough to eventually put him on the sympathetic side of those who marched for civil rights and protested the Vietnam war.

"I came out of what was almost a 19th century background, and it was framed by faith, family and the extravagant public rituals of New Orleans."

His college career began at Loyola University New Orleans in 1967. With his transfer his sophomore year to Georgetown University, his emergence into the 20th century was complete. "Georgetown was a new world. Reading the [Washington] Post every morning was an education in itself. The Civil Rights movement had a greater urgency in Washington."

The English department at Georgetown worked on the great books approach. "It was the grand tour of Western literature. I don't think I read Hemingway until I got out of college; I know I didn't read Faulkner there."

During an entire semester on Milton, he "fell in love with Satan, what a great character. I speak in a literary sense."

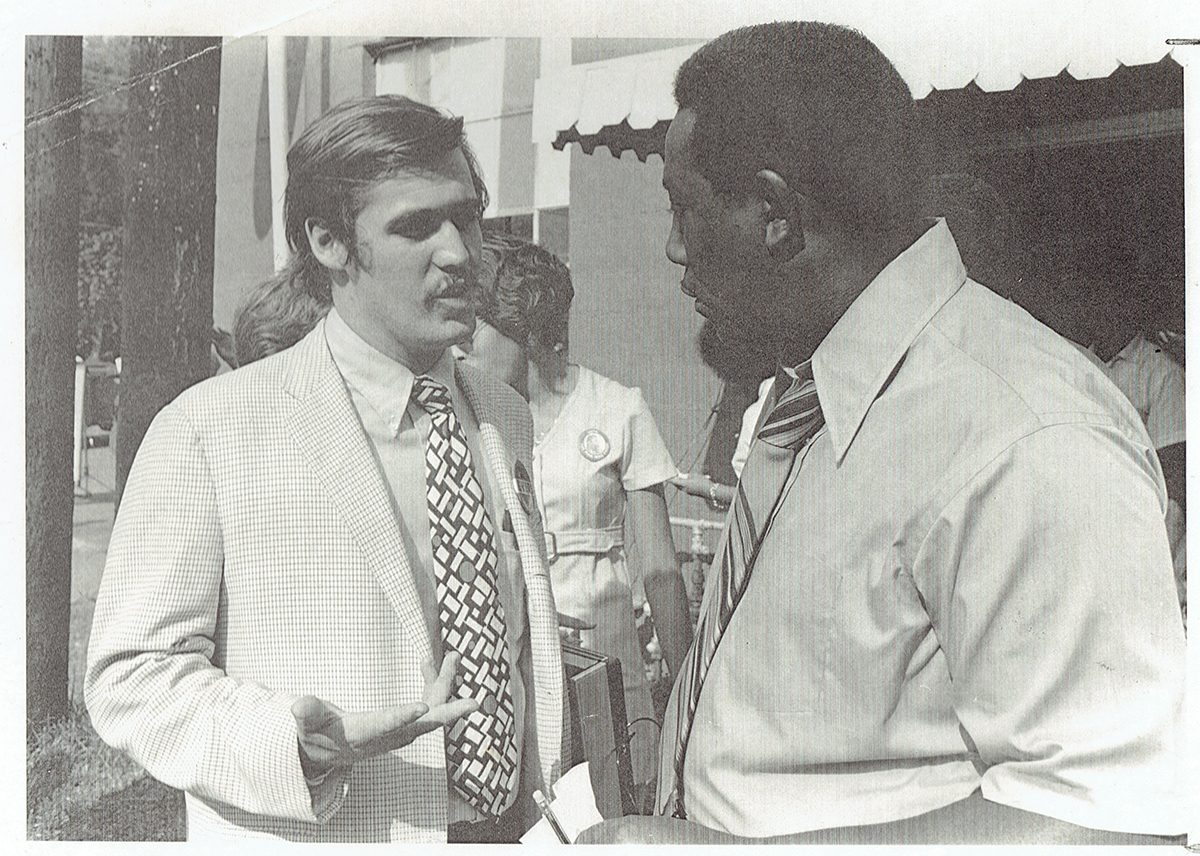

Berry volunteered with Charles Evers' (right) 1971 campaign for governor of Mississippi. (Provided photo)

With Georgetown degree in hand in 1971, the young man who would work ungodly hours over a lifetime while never holding a conventional full-time job, headed directly for Mississippi and spent the summer after graduation as a volunteer in the longshot gubernatorial campaign of Charles Evers. "I wanted to be part of the movement for changing the South. And it was an eye-opening and almost life-dividing experience."

Evers, whose brother Medgar was assassinated by the Ku Klux Klan in 1963, lost by a large margin, "but we managed to elect 52 African Americans to local office, which was a real breakthrough for Mississippi," said Berry. "It was the first major test of the black vote following the 1965 Voting Rights Act."

Berry then spent "10 months writing in a white heat after the campaign" and had his first book contract within a year of graduation.

Southern novelist Walker Percy, whose works were often set in New Orleans, had seen a piece Berry had done on the politics of the South for the Vieux Carré Courier, a French Quarter alternative weekly. "I was sitting there working away one day in August when the telephone rang and it was Walker Percy. I almost had heart failure that he would call me." Percy put him in touch with an editor at Saturday Review Press.

Amazing Grace: With Charles Evers in Mississippi was published in the fall of 1973.

Berry took the advance money from that book and in December 1972 went to Europe for several months, spending some of that time in Paris where he became fascinated in a new way with his home city of New Orleans, the one he felt compelled to leave just a few years earlier.

It became apparent that the dream of the freelance correspondent life in Paris was beyond reach. "I had no tools; I couldn't get hired." But he kept noticing eyes lighting up in fellow American wanderlusts when he would answer endless rounds of "Where you from?" with "New Orleans."

"I realized that there was a lot about New Orleans — a whole side of it — that I didn't know. And that, in large measure, is what prompted me to go back."

From people who had never lived in New Orleans, Berry began to understand what he never saw growing up there, that "it was a place of mystery and intrigue … it had a certain mystique."

Back in New Orleans and scraping by on freelance wages, he was beginning to get work placed in national publications, book reviews for the New Republic and articles for The Nation.

He did a major piece with backing from the Fund for Investigative Journalism, revealing that the IRS had audited 27 black leaders in Mississippi. It was published in 1975 in the Delta Democrat-Times, a progressive paper run by Hodding Carter III, best known for his later role as undersecretary of state for public affairs for President Jimmy Carter.

During that period, Berry was also writing a lot of fiction, "the brilliance of which eluded New York publishers" and pulling all-nighters "writing novels that never saw the light of day." He was also moving into videotape work, which led to production of a documentary and book of the same name, Up from the Cradle of Jazz. The documentary aired in 1980 on Louisiana Public Broadcasting. The book, done with co-authors Jonathan Foose and Tad Jones, was published in 1986.

Legendary New Orleans street musician Doreen Ketchens (Unsplash/Nathan Bingle)

In hindsight, the dual track of his life is obvious: an instinct for the journalistic deep dig and an ear attuned to the soul of New Orleans.

In 1982, newlywed Berry and his first wife, Lisa LeBlanc, put all of their possessions in storage and headed to Europe.

When the couple arrived in Paris following travel in Italy and elsewhere, they found out that Berry had been accepted into a program called Journalists in Paris, a 10-month language school and travel program. On the side he did pieces for Readers' Digest (on how airline luggage retrieval systems worked) and for the International Herald Tribune. "We managed to make a go of it for about 15 months, and then came back."

That marriage ended in divorce in 1996. They had two daughters, Simonette, a graduate of Tulane University in studio art, and Ariel, who died at age 17 in 2008 of heart failure and complications from Down syndrome.

The couple moved back to New Orleans from Paris just in time for him to finish work on Up from the Cradle of Jazz and, in the fall of 1984, see the first news about Fr. Gilbert Gauthe, a serial pedophile and a priest of the Diocese of Lafayette, Louisiana. That news would change the course of Berry's life.

Exposing the abuse crisis

Lead Us Not Into Temptation: Catholic Priests and the Sexual Abuse of Children, was published by Doubleday in 1992, seven years after Berry's original work about Gauthe appeared in 1985 in the Times of Acadiana and the National Catholic Reporter, and fully 10 years before the Boston Globe's spotlight reports documented the abuse in the Archdiocese of Boston.

Those earliest accounts from the mid-1980s are journalistically cautious and measured, though detailed and precise. The pieces make for deeply disturbing reading, breath-catching in their preposterous newness. Most Catholics of the time couldn't imagine priests doing what Gauthe, a serial pedophile, had done to children with whom he came in contact.

By the early 1990s, Berry had done enough of the type of reporting required to construct the distinguished narrative that elevates his work above many others. The opening scenes of Lead Us Not Into Temptation are darkly riveting, understatedly infused with the pain and rage of parents becoming aware that a favorite parish priest, someone who sat at their table and who had taken three of their sons, all altar boys, on camping trips, had been repeatedly molesting those youngsters for years.

It was shoe-leather journalism of an era that preceded data bases and email and the nervous flutter of social media. Berry conveys anguish understood by way of hours of interviews and conversation and firsthand observation, wrenching as it was. He describes, conversation by conversation, what would later become recognized as the Catholic institutional preference for protecting the perpetrator over concern for child victims.

Berry with theologian Hans Küng in 2012 (Provided photo)

His work on that 1984 case in Louisiana broke open what the sociologist priest Andrew M. Greeley described in the intro to the 2000 paperback edition of Lead Us Not into Temptation as "The greatest scandal in the history of religion in America."

It is easy to speculate that were Greeley alive today he would amend that comment to reflect that the scandal has gone global and is yet bedeviling church leaders.

"He was the Woodward and Bernstein altogether," said David Gibson, an award-winning journalist and author who now heads the Center on Religion and Culture at Fordham University, referring to the legendary investigative reporting duo of the Watergate era. "He was the shoe leather that doggedly constructed the narrative of the scandal piece by piece."

Berry represented, said Gibson in a phone interview, "what real investigative reporting involves. Everyone wants to go for the brass ring, the big expose, but that's not the way it normally works. Classic investigative reporting involves reporting this one thing. And then the next, and the next."

Said David Clohessy, co-founder of SNAP, the abuse victim advocacy group, "No single reporter anywhere has done more to expose — and thus help to remove — this horror from the church. For years, it felt like he was practically the only journalist who took victims seriously and listened to us compassionately. And he was perhaps the first reporter to recognize that we were more than isolated victims but in fact a potential collective force for good, as we started in the 1980s and 1990s to organize ourselves first into support groups and then into advocacy work."

"He was the first to look at the crisis in a broader way, as more than a handful of 'bad apple' priests and to look at bishops' self-serving claims with a careful eye," Clohessy said.

Being the first wasn't easy. Berry was watching the story develop bit by bit in minimal accounts in local media and felt there was need for a deeper dig suitable to a national outlet. He knew lawsuits were piling up in Lafayette. "How many other kids were out there?" he asked. He tried a number of national publications: The New York Times, The Washington Post, Vanity Fair, The Nation, Mother Jones. No takers.

He did four months of investigation on his own in early 1985 before calling Linda Matys, then-editor of Lafayette's weekly, The Times of Acadiana. She was interested, offered a month's salary and expenses, as well as permission to publish reports in national outlets after they appeared in the local paper. Before heading off to Lafayette to continue his research, he called Thomas C. Fox, then-editor of National Catholic Reporter. Berry had been told of NCR by someone at the Fund for Investigative Journalism, which had also rejected his proposal seeking funds.

Fox, who since has served as publisher and is currently CEO/President of NCR, said the publication had begun gathering similar information from other parts of the country "though not in any systematic way."

In Lead Us Not into Temptation, Berry wrote that Fox cautioned the church "was not subject to the same checks and balances as a government." But that "if child abuse had crept into that tradition and could be proven, NCR would report it."

"This is an important story," he quoted Fox in the book "but as a loving critic of the church, I want it done in a way that will spur the hierarchy to act responsibly. We don't have to pull punches, but there has to be a motive beyond sheer exposé."

By the time Berry began work in earnest for The Times of Acadiana, he knew that reports of priests molesting youngsters, and of possible cover-up, had surfaced in at least several states. This was different from a run-of-the-mill corruptions story. "The violation of children by men in the church was something I couldn't walk away from. And I kept getting more and more leads," he told me.

What followed is a saga that, 34 years later, is nowhere near running its course. The original exposé that appeared in the Acadiana paper was the basis for a four-page spread in June 1985 in NCR. Berry continued to dig, and to write and report, and long before it became a story widely believed, he knew that its tentacles spread globally and to the highest echelons of church governance.

Exposing the Maciel scandal

One of the most notorious figures of the abuse scandal in the Catholic Church was Marcial Maciel Degollado, a Mexican cleric, founder of the highly regimented Legionaries of Christ, and an enormously successful fundraiser. Maciel was a caricature of overweening piety with breathtaking amounts of cash to throw around the Vatican. He also enjoyed a certain insulation against investigation of numerous substantial accusations of horrific sexual abuse of minors because he was a favorite of Pope John Paul II. Consequently, he was also the favorite of John Paul's highest profile acolytes in the United States, who ridiculed and dismissed the reporting of Berry and his friend and colleague, the late Gerald Renner, when, in articles published in 1996 in the Hartford Courant, they began to expose Maciel and the practices of the Legion.

Pope John Paul II blesses Father Marcial Maciel Degollado, founder of the Legionaries of Christ, at the Vatican in 2004. (CNS photo/Reuters /Tony Gentile)

Eventually, the truth caught up to Maciel, a predatory abuser who also fathered several children by different women. Under Pope Benedict XVI, an investigation went forward, and he was confined in 2006 to a life of private prayer and penance. He died in 2008.

The world came to know about the hypocrisy and crimes of Maciel through the reporting of Berry and Renner, who was then a religion writer at the Hartford Courant. That paper carried the Berry/Renner initial reporting about the Legion in the United States. Berry wrote extensive pieces for NCR,published in 2010, about Maciel and the influence his money was able to leverage at the Vatican.

In March 2002, Fr. Richard John Neuhaus, one of the principal intellectual authors of the religious right in the United States, wrote a scathing and quite personal condemnation of Berry's and Renner's initial reporting on Maciel.

Neuhaus, who died in 2009, had already thoroughly disparaged and largely dismissed Berry's early reporting on the crisis in a lengthy review of Lead Us Not into Temptation, his first book about the scandal. The review appeared in the January 1992 issue of First Things, a magazine Neuhaus founded. He gave only grudging concession to the factual accuracy of Berry's accounts. The scandal did not fit the narrative preferred by Neuhaus and his followers, and he insisted on blaming most of it on the influence of homosexuality in the priesthood, an assertion debunked by most professionals and eventually in an extensive 2011 study of the situation by investigators at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice.

The late Richard John Neuhaus is pictured in this 2005 file photo. (CNS photo/Bob Roller)

In the 2002 review, Neuhaus slammed the work of Berry and Renner, as well as NCR, which ran an account of the Courant reporting, as trading in rumor and slander. He called the reporting "an attack" on Maciel, "the much revered founder of the Legionaries of Christ, one of the more vibrant and successful renewal movements in contemporary Catholicism."

In thousands of words, Neuhaus continued his blistering personal attack on the journalists, demeaning their work, condemning them as motivated by hatred of the church and working every angle to erode their credibility. Neuhaus concluded: "I have arrived at moral certainty that the charges are false and malicious [emphasis in the original]," he wrote. For emphasis, he added that the charges "should be given no credence whatsoever."

At the time, Neuhaus' reputation was yet untainted by the facts that eventually showed him to be as wholly incorrect as he was morally certain. At the time, his moral bluster created quite a headwind against which Berry and others had to fight to keep reporting honestly about Maciel and the Legion.

In the long haul of the story, the insistent denial by Neuhaus and others sank beneath the enormity of the evidence, which continues to accumulate to this day, of what Berry repeatedly referred to in our conversations as institutional mendacity. More simply, bishops lied and covered up, and he knew it. Today, he "shrugs," he says, at the displays of breathless ongoing "discovery" of old evidence that continues to demonstrate the degree to which the hierarchical structure is corrupt and incapable of confessing its own sin.

It took him six and a half years to research and write Lead Us Not into Temptation. The book was rejected by 30 publishers. It had been to different editors twice at Doubleday, but finally found a home there when Greeley, who had been reading chapters for Berry and giving him reactions, paved the way to yet another editor at Doubleday, and he took it on. Berry said his agent at the time "told me on several occasions that he sensed that editors were skittish on reading it. That they feared their publishing company would be sued by the church."

But "things were starting to shift" in 1991 as the public was slowly coming to terms with the scandal, and the book, finally published, caused quite a stir and landed Berry on a lot of national TV news shows to talk about it. "I guess in a sense the long struggle with the reporting and to get it published was vindicated."

Back to New Orleans

"As the marketplace took root, Africans used the land to dramatize their past, resurrecting burial choreographies of the mother culture. The living danced their tributes to the dead in sinuous rings. Moving to the rhythms of strings and hide-covered drums. As time passed and crowds grew, the dancers formed concentric circles, rings within rings. Several hundred people at a time flow to spirit tides that surged out of the past."

— City of a Million Dreams

Berry's CV runs to 20 and a half pages, starting with 10 books — including one quite nicely done novel that did make it beyond his study, Last of the Red Hot Pappas — a one-man play, Earl Long in Purgatory, five documentaries, a full page plus of awards and honors, pages listing his major work published in scholarly journals as well as mainstream outlets. (Between the CV list, which runs to 2012 and what's appeared on the NCR website since, I counted at least 47 pieces that have run in this publication.) He also lists two pages of grants and fellowships from an array of foundations and funds. Berry's prolific output is matched only by the amount of time and energy he's had to spend hustling for the money to make the projects possible.

Asked if he's ever held an actual job, he paused long, lips moving slightly as he silently ticked through the catalogue of accomplishments. "No," he answered.

In 2004, Berry married Melanie McKay, who recently retired as vice provost for academic affairs at Loyola University New Orleans, where she also taught English for many years. She once suggested he return to school and acquire an additional degree so that teaching might be a fallback position. But, he said, "I had no interest in teaching at all." So he kept scrambling and writing.

The demands of investigative reporting — as Gibson put it, first one thing, then the next, and the next, fact linked to fact — leave little room, beyond raising the next logical question, for moving beyond the evidence. It is a meticulous enterprise.

History, at least of New Orleans, and even in describing above the activity of slaves in transforming a patch of land, provides space for Berry's more lyrical side, and he deploys it with an accomplished hand. There is an accompanying documentary, which bears the book's title, co-produced with his daughter, Simonette. An explanation by Berry and a trailer introducing the documentary can be found here.

A street band in New Orleans (Unsplash/ Robson Hatsukami Morgan)

Foreward Reviews termed the book "a hypnotic biography of a unique American city."

Wrote NCR's reviewer: "Drawing upon the best scholarship in military and political history, culture, music, food and urban geography, Berry's resources offer delightful insight into the vast mosaic that is this global city."

It was a formidable enough work to earn a review by Garry Wills in The New York Review of Books, an examination that validated Berry's ambition. Wills moves from one fascinating character to the next in what he describes as Berry's technique of "overlapping narrative."

Starting with the city's flamboyant founder, Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville, then traveling through 18th century monks and church disputes that pre-shadow the current era, through musicians and politicians and spiritualists of every imaginable stripe, and through the devastation and resurrection out of Hurricane Katrina this is, indeed, a breathtaking guided tour through an American city that can't begin to be captured in travel brochures. It's just too quirky, too out of the mainstream narrative of settlers and rugged individualism.

"I wanted to understand the place where I'm from," said Berry during his presentation at the bookstore in Washington. "I figured the best way to do that is to understand the daily life of people across the first three centuries."

As so many times before in the course of his own character-driven journey, he figured correctly.

[Tom Roberts is NCR executive editor. His email address is troberts@ncronline.org.]