Operations at Cribari Vineyards in Fresno, California, came to "a dead halt" as COVID-19 shutdowns spread across the U.S. With only priests primarily consuming the consecrated wine, the need for greater quantities disappeared, and many churches relied on in-house inventory. (Courtesy of Cribari Vineyards)

2022 was supposed to be a big year at O-Neh-Da and Eagle Crest Vineyards.

The winery, tucked in the hills and valleys of upstate New York's Finger Lakes region, is preparing to mark its 150th anniversary, a milestone reached by few vineyards nationwide under its original name. A further distinction, it's one of the few vintners of sacramental wine in the U.S., and perhaps the only one with production of the grapes that become the Precious Blood as its core business.

"This was going to be a big year for us," said Will Ouweleen, who runs O-Neh-Da with his wife, Lisa. Celebrations were planned, and momentum was at their backs as, businesswise, "we had our best year in 2019, ever."

"And then the pandemic struck."

In the days after the World Health Organization declared the SARS-CoV-2 virus a pandemic on March 11, 2020, Catholic parishes and churches across the country and around the world closed their doors and temporarily ceased in-person celebrations of the Mass in lieu of virtual liturgies. When churches reopened, in most cases the communal Communion cup did not come back.

For cultivators of sacramental wine, it represented a worst-case scenario. And as concerns remain about how to conduct communal consumption of the Precious Blood amid a highly contagious virus, so too winemakers worry about what those decisions will mean for their future business.

"We had our best year in 2019, ever. And then the pandemic struck," said Will Ouweleen, vintner in Conesus, New York, at O-Neh-Da Vineyard, which had produced sacramental wine for 150 years. (Courtesy of O-Neh-Da Vineyard)

"Even if the church returns to the common chalice being distributed, I don't think a lot of people are going to take it up," Ouweleen said.

"I don't even know if it'll ever come back again," said John Cribari, president of Cribari Vineyards in Fresno, California. "I don't know. Would you do it?"

Sales down 90%

Operations at Cribari came to "a dead halt" as COVID-19 shutdowns spread across the U.S.

The vineyard, located in California's Central Valley, the top grape-growing region in the state, had just scheduled a large packing order to prepare for Easter — along with Christmas, one of the biggest business days, as churches anticipate more people filling the pews.

"When we saw what was coming, we just threw a huge wrench into the schedule of production and cut it substantially," Cribari said.

With only priests primarily consuming the consecrated wine, the need for greater quantities disappeared, and many churches relied on in-house inventory.

Advertisement

A similar scene played out nearly 300 miles south at Joseph Filippi Winery and Vineyards in Southern California. Sacramental wine sales in the region, which normally make up around 35% of purchases, plummeted.

"I don't bother looking at those numbers, because it's just disheartening," Joseph Paul Filippi, president and fourth-generation winemaker, said. "I'm busy trying to get business back and make more business."

In late February 2020, Archbishop Leonard Blair, chair of the Committee on Divine Worship for the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, sent a memo to all bishops outlining health precautions to curb the spread of the novel coronavirus. Among the guidelines in the memo, a copy of which NCR obtained, was suspending the distribution of holy Communion to the congregation via the chalice.

Another set of recommendations, issued April 30 that year, stated as churches looked to begin reopening, distribution of the Precious Blood should remain paused, "nor should the faithful receive the Eucharist by intinction" — dipping the host into the consecrated wine. Nearly every diocese in the U.S. adopted the measures, and the communal cups were mothballed.

'Even if the church returns to the common chalice being distributed, I don't think a lot of people are going to take it up.'

—Will Ouweleen

Respiratory viruses can transmit from one person to the next as germs are spread through the air, by touch and on surfaces, said Enbal Shacham, a professor of public health at the St. Louis University College for Public Health and Social Justice, the country's only accredited Catholic school of public health.

With COVID-19 far more contagious and deadly than the flu or common cold, the risk of transmission is greater, spurring public health officials to recommend preventative measures like sanitizing surfaces, limiting large gatherings, wearing masks and avoiding shared items, including a cup.

"The major point of contact, from one mouth to the next mouth, it doesn't get very much more intimate than that," Shacham said.

Along with sacramental wine vineyards, wholesalers of church supplies and goods also saw business dry up fast, not just for sacramental wine but other items like hosts and candles. Patrick Baker & Sons, which primarily distributes Mont La Salle altar wines in New England, saw its overall sales cut in half. At the Church Supply Warehouse, based in Wheaton, Illinois, sacramental wine sales made up 10% of sales pre-pandemic, and have shrunk to roughly 1-2% of total revenues.

A promotional photo for Mont La Salle Altar Wines produced in Napa, California (CNS/Courtesy of Mont La Salle Altar Wines)

For Cribari, which began making altar wines during Prohibition and sells throughout the country, its drop in sales halted altar wine production in 2020. It resumed the next year, but mainly for customers in Europe.

As the pandemic roiled on, both California wineries faced other challenges, too, including labor shortages or heat waves and droughts exacerbated by climate change. Still, what helped buoy business were their table wines, which make up the bulk of sales. Industrywide, retail sale of wine, beer and liquor jumped 20% during the pandemic's first seven months.

"If we had to live off the altar wine program, it would be very difficult," Cribari said.

But that's the case at O-Neh-Da.

For the New York winery, founded by Rochester Bishop Bernard McQuaid, altar wine sales are roughly 90% of its business, selling directly to about 2,000 churches in New York and Pennsylvania. It used to be 100%, until the Ouweleens, who took ownership in 2007, began producing a line of table wines. But even in the best years, like 2019, those made up no more than 10% of total business.

That October, Ouweleen had harvested 40 acres of grapes when he watched a virology conference that mentioned a potential worldwide pandemic. The news was compelling enough he decided not to order $250,000 in glass he would typically use to bottle in the spring. That move helped save his business, as it went from its best year to its worst with sales down 90%.

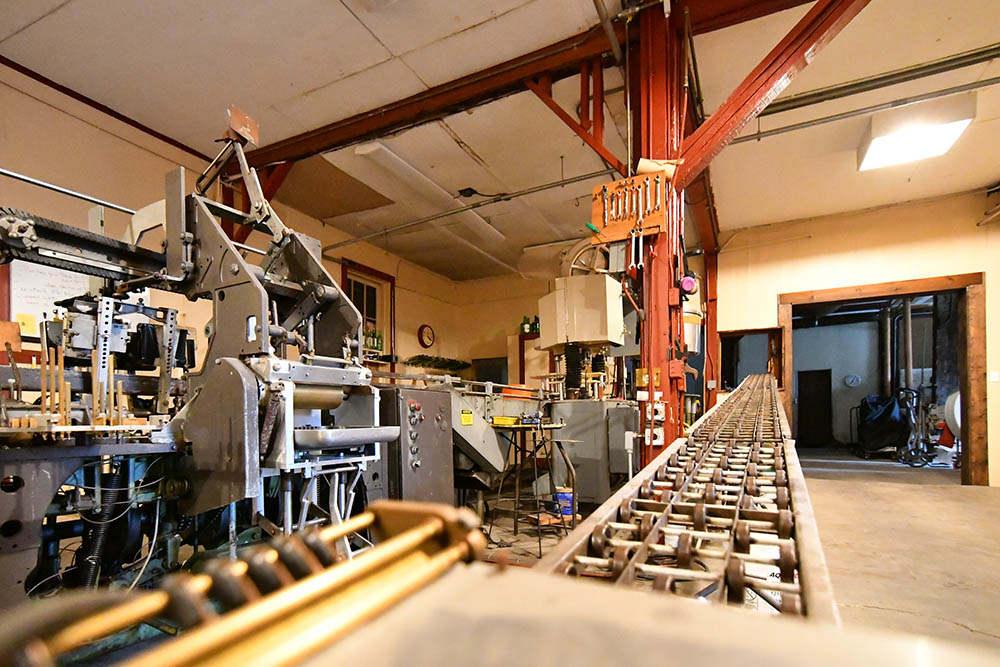

When the COVID-19 pandemic was declared in March 2020, the bottling line at O-Neh-Da Vineyard, in New York's Finger Lakes region, grinded to a halt as church demand for sacramental wine dried up as distribution of the Communion cup has paused. (Courtesy of O-Neh-Da Vineyard)

O-Neh-Da did not harvest in 2020 or 2021, and the 30,000 gallons of wine from 2019 continues to sit in chilled stainless tanks. As Ouweleen and the wine wait, he has drawn some hope from the vineyard's long history, having survived past global calamities like the 1917 Spanish flu outbreak, Prohibition, the Great Depression and two world wars.

"The grace of God will carry us through, and that's my operating premise," he said.

Theological concerns

The situation facing the fate of the Communion cup is one Catholics haven't really faced before.

In the Catholic Church, the laity sharing from the chalice is only a recently resurrected experience. While early Christians consumed both species — the body and blood of Christ — at the Eucharist, the practice stopped in the late Middle Ages, primarily over concerns with spilling, said Susan Ross, an emerita theologian at Loyola University Chicago. Restoring the cup to the laity became a focus of Martin Luther and the Reformation, which Protestants ultimately did in 1558.

"But it was really not until Vatican II that the practice changed [in Catholicism] and then people began receiving under both the bread and the cup," Ross said.

At the Second Vatican Council of the 1960s, church fathers addressed the Precious Blood in Sacrosanctum Concilium, the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy. Ross said there was an emphasis "to return to the roots of liturgy," including people receiving the Eucharist through both consecrated species. The expression represented a pivot from a priest making the sacrifice for the people to a more shared, communal experience of the sacrament.

Pope Francis elevates the Eucharist as he celebrates Mass at the GSP Stadium in Nicosia, Cyprus, Dec. 3, 2021. (CNS/Paul Haring)

"By restoring the cup to the people, it helps to promote that full, conscious and active participation and gives us a fuller sense of celebration as the Mass is intended to be," said Jesuit Fr. Thomas Scirghi, a theologian at Fordham University who specializes in liturgy and sacraments.

Fr. Dustin Dought, associate director in the U.S. bishops' Secretariat of Divine Worship, said that since Vatican II the church has emphasized that while the distribution of both host and wine "more fully expresses Christ's gift of himself at the Last Supper," the fullness of sacramental grace is present in each species.

"When it comes to the sign, the sign is less full, the expression is less full. But when it comes to grace, there's no deprivation of grace," he said.

The availability of the consecrated wine is especially important for people unable to receive the host, for example due to a gluten intolerance. Ross called it "a prudential decision" to withhold the cup during the pandemic. At the same time, it can still feel like something is missing from the Mass.

'Not being able to receive the eucharistic wine, I think, does feel like a loss for people, because it is one less palpable symbol of the real presence of Christ.'

—Susan Ross

"Not being able to receive the eucharistic wine, I think, does feel like a loss for people, because it is one less palpable symbol of the real presence of Christ," she said. "But it's a recognition, of course, that we have to deal with reality as it is."

Suspensions of the Precious Blood are not new for sacramental winemakers. Such suspensions have occurred every few years when a particularly contagious flu virus emerges. In the divine worship committee's February 2020 memo, Blair noted similar advice was offered in 2009 related to the H1N1 "swine flu" pandemic.

What has made COVID-19 worse than past pauses has been its endurance, as the pandemic recently surpassed its two-year mark and has eclipsed 6 million deaths worldwide. With that longevity has come uncertainty.

Even as COVID-19 cases have dropped in recent weeks across the U.S., and more and more states have lifted restrictions and mask mandates aimed at limiting spread of the virus, churches are moving cautiously in how they approach the Communion cup.

A majority of Catholic dioceses remain in a wait-and-see period, and the cup continues to be suspended indefinitely in most places. That's the case in the archdioceses of New York, Los Angeles and Chicago, as well as dioceses of Sacramento, California — just east of Napa Valley — and Rochester, New York, where O-Neh-Da is located. Both the Chicago and L.A. archdioceses told NCR they have begun discussions about reintroducing the Precious Blood to lay Catholics at Mass.

Bishop David Talley raises the host during his installation Mass at the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception in Memphis, Tennessee, April 2, 2019. (CNS/Courtesy of Memphis Diocese/Gragg Higginbotham)

On Feb. 28, Bishop David Talley of the Diocese of Memphis, Tennessee, announced he will lift COVID-related restrictions, including withholding the Communion cup, beginning April 14, Holy Thursday. Talley said it would be up to each priest to decide when to bring it back. The diocese did not respond to an interview request about the decision.

Dought told NCR the divine worship committee hasn't had discussions about when or how to bring back the cup and that it is not planning at this time to issue further guidance to dioceses, saying the decision is for each bishop to discern.

The question isn't just whether the cup will return, but if people will feel comfortable sipping from it.

Shacham, the St. Louis University public health professor, noted that the coronavirus pandemic has led people and communities to think more critically about infection control generally and to reassess long-standing behaviors.

"This is an opportunity for us to reevaluate how risk-averse or risk-accepting are we in different settings," she said.

One option that could become more prevalent, and that some priests during concelebrations have turned to during the pandemic, is intinction, a practice more common in other countries where it is culturally taboo to share the same cup.

"As diocesan bishops are discerning the distribution of Communion and what that looks like, I think that's going to be part of their discernment," Dought said.

One idea likely off the table? Individual cups.

While common in some Protestant churches, the theologians who spoke with NCR said it was less a fit for Catholics. First, the more cups there are, the greater chance of spilling the Precious Blood. Then there's the question that Indiana Jones famously faced: What's a worthy vessel? But above all, they say it's a matter of symbol of what the Eucharist represents.

"The community becomes one by sharing in the one chalice. And to have individual chalices diminishes the sign of unity, of communion, I think," Dought said.

Fr. Chinthaka Perera gives the Communion cup to a woman during Mass at St. Boniface Martyr Church in Sea Cliff, New York, April 25, 2019. (CNS/Gregory A. Shemitz)

He added that the reception of both species at holy Communion will be "a big part" of the bishops' forthcoming National Eucharistic Revival, in terms of highlighting the importance of the wine as much as the host.

Will people take the wine?

As bishops and parish priests discern the future of the Communion cup, makers of sacramental wine are anxiously waiting.

The return of the cup is only one part of the equation, they say. The other is whether people will come back to church in the same numbers as before the pandemic, and even if they do, how many will opt to receive the chalice with health concerns more prominently in mind?

"I think that's even a greater challenge for the churches that we serve, is getting people to return to Mass," Ouweleen said.

It's a question so far without an answer, as data remains scant on Mass attendance, partly because not all churches have fully reopened and partly because the pandemic isn't over.

Count Scirghi among those worrying about how the church will transition back to in-person liturgies. The convenience of attending Mass by Zoom has allowed people to connect with their faith during a time of social distancing, but it also makes the Eucharist inaccessible.

"I see some definitely coming back and many want to come back gradually. But the churches are not as full as they were before," Scirghi said.

How, and how many, people return to Mass is of major consequence for the vineyards producing sacramental wine.

O-Neh-Da Vineyard has produced sacramental wine for 150 years in New York's Finger Lakes region. (Courtesy of O-Neh-Da Vineyard)

At Cribari Vineyards, the pandemic has more or less put a halt to their larger, four-liter jugs, which are more popular with churches with large congregations.

"We're just currently selling the bottles, because that's all people are buying," Cribari said, adding that if Communion under both species resumes they'll look to selling jugs again.

At this point, Cribari, which distributes primarily through Catholic retail stores, sales are about half of pre-pandemic purchases. As churches have reopened, and people slowly coming back, orders have slowly bounced back for church goods wholesalers, too, but sacramental wine continues to sag behind.

Sacramental winemakers have asked their church customers about when the communal cup might return, in order to make harvesting plans and ordering materials, as prices for glass and labels have skyrocketed in the supply chain crunch.

In the months after the pandemic was declared, Ouweleen sent letters to bishops in New York and Pennsylvania, two of O-Neh-Da's main markets, as well as the bishops' conference to try to get a sense of when full Communion may come back. The responses he received carried the same refrain: not for the foreseeable future.

In recent years, O-Neh-Da Vineyard, which runs on solar power, expanded its business in New York's Finger Lakes region to offer table wines, welcome campers and host events. (Courtesy of O-Neh-Da Vineyard)

In the time since, he's looked for ways to make do, dubbing 2022 "the great pivot."

Taking advantage of his scenic location on Hemlock Lake, he's opened glamping — "glamorous camping" — at the vineyard and rents out a guesthouse on Airbnb.

Ouweleen is also looking for his altar and table wines, all produced through natural and sustainable processes, to capitalize on consumer trends toward organic goods and buying local, whether for parishes or wine parties.

And the plans for the 150th year celebration continue, including music events and a sustainable farming symposium.

Beleaguered by the pandemic, the Ouweleens are ready to turn the page. Guided by their motto for the year, "Love wins," they hope their wines can be a part of a more positive energy in the country that brings people together again.

Whether at their vineyard, or in the Communion line.

"I remain faithful and hopeful," Ouweleen said. "And beyond Communion, I just hope our world can get back to a more loving, unified place."