Participants talk during a July 19 breakout session of the Pan-African Catholic Congress on Theology, Society and Pastoral Life, which took place July 18-23 in Nairobi, Kenya. (NCR photo/Christopher White)

An old African proverb says that "until the lions have their own historians, the history of the hunt will always glorify the hunter."

A second gathering of the Pan-African Catholic Congress on Theology, Society and Pastoral Life, which took place in Nairobi in July, showed that the lions are not only writing their own history now, but they are shaping their future — and also that of the global Catholic Church.

In 1900, an estimated 2 million Catholics lived on the African continent. Today, that number stands at about 236 million.

And the common sentiment expressed during the July 18-23 gathering at the Catholic University of Eastern Africa is that the ones who were once evangelized must now become the evangelizers.

That was certainly the desire of Pope Francis, who sent a video message to participants, expressing his hope that "paths emerge from this congress that the church needs: paths of missionary, ecological conversion, peace, reconciliation and transformation of the whole world."

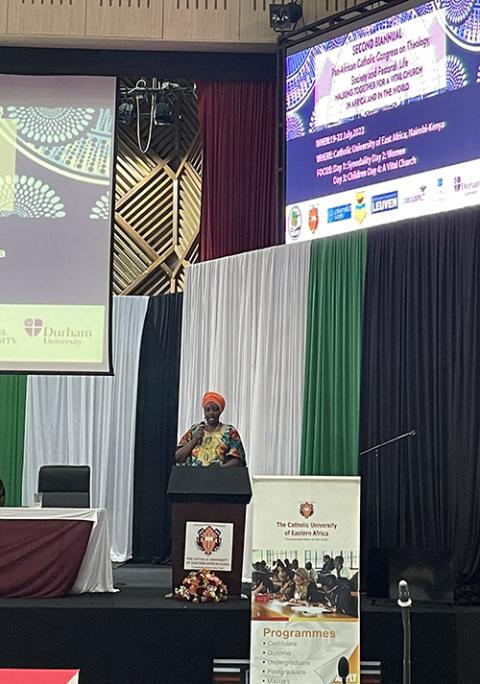

Precious Blood Sr. Mumbi Kigutha, organizing secretary of the Pan-African Catholic Congress on Theology, Society and Pastoral Life, speaks July 20 during the gathering in Nairobi, Kenya. (NCR photo/Christopher White)

More than 100 pastoral leaders and interdisciplinary scholars from more than 20 African countries and five continents met in the Kenyan capital for the second congress organized by the Pan-African Catholic Theological and Pastoral Network, with a theme of "Walking Together for a Vital Church in Africa and in the World."

At the outset, Kenyan Precious Blood Sr. Mumbi Kigutha, organizing secretary of the congress, told NCR that the goal was to put everything on the table — even the sometimes taboo topics, such as clericalism, the role of women and LGBT persons, that are often off-limits in the African church.

The six days of discussion did just that, with sessions on domestic violence, war, economic and ecological crises, child sexual abuse, human trafficking and more — all against the backdrop of the Vatican's revamped global synodal process, meant to facilitate greater participation of Catholics throughout the world.

By the end, a joint declaration was approved, stating: "The urgent and complex social problems that afflict us show how important it is that the synodal spirit — 'walking together' — becomes a source of inspiration for ethical, ecclesial, and political commitments."

And in between, according to DePaul University theologian William Cavanaugh, the congress demonstrated that "there's an openness to the future here, rather than looking backwards."

Palaver as synodality in action

Synodality has long been a difficult word to define — and not just for Catholics. But in Africa, as congress participants repeatedly attested, another word for synodality might be palaver.

Palaver, which takes its origins from the name of the tree under which traditional African communities would gather to discuss issues of importance, is the philosophical method that shaped both the first-ever Pan-African Catholic Congress (which took place in Enugu, Nigeria, in 2019) and its latest iteration in Kenya.

Historically, the palaver method has emphasized a sharing of ancient wisdom to find practical, peaceful solutions in confronting sometimes divisive issues of the day, in which everyone gets a chance to have their say.

A plenary session of the of the Pan-African Catholic Congress on Theology, Society and Pastoral Life on July 20 in Nairobi, Kenya (NCR photo/Christopher White)

So, too, according to conference participants and organizers, is synodality at its best.

Addressing the conference via video, Cardinal Mario Grech, secretary general of the synod, told participants, "The religious, cultural, philosophical traditions of Africa have such rich resources, examples and values and practices that really can correlate with the concept of synodality."

"The synodal spirit is alive in Africa," he said, "rooted in the diverse and inculturated ways of being church in local contexts."

Numerous conference attendees attested to this reality, saying that the synodal process was something felt and experienced not just at the levels of leadership in the church, but in the pews of churches and beyond.

Nairobi Archbishop Philip Anyolo told NCR that in his archdiocese, the goal was to include in the synod process not just Catholics but other Christians and those outside of the church. He said that of the 5 million people who live in Nairobi, more than 2 million had participated, mainly through listening sessions over the last year held throughout the Kenya capital.

Because of synodality, 'I have the opportunity to explain to a clergyman, a priest, what it means to be a woman in the Catholic Church.'

—Nora Nonterah

Similarly, Kenyan St. Joseph Sr. Leonida Katunge, who is both a theologian and a civil lawyer, said that she was impressed that the official prayer for the synod was still being prayed regularly at local parishes throughout the city and that posters for the synod continue to fill the churches.

She noted that part of the reason for the widespread enthusiasm among the laity is that "we have lived in a church of clericalism."

"This is what we have been called to change and also appreciate the fact that we have been invited as protagonists," she told NCR.

That spirit has rippled across the continent, said Ghanian theologian Nora K. Nonterah.

"Synodality simply means all of us working together, walking together, doing things together by recognizing that we all, by virtue of our baptism, are called to the same responsibility," she said. "As a laywoman in the church and a theologian, synodality means everything to me."

Outside the entrance of the Catholic University of Eastern Africa in Nairobi, Kenya (NCR photo/Christopher White)

She believes the essence of synodality can be seen in the palaver approach, which was modeled at the congress, with Catholics from various backgrounds, titles and functions seated at the same table.

"Because of this approach, I have the opportunity to explain to a clergyman, a priest, what it means to be a woman in the Catholic Church," she said.

"That is what synodality actually means," Nonterah added. "The ability for all of us to come from wherever we are to meet each other at a point where we can have conversations about what's happening in the church and be able to say, 'In the spirit of synodality, may I say this.' "

Combating 'sacerdotal megalomania'

Yet if synodality has helped usher in a new way of being church, congress participants were not shy in naming the ecclesial problems they see needing a course correction.

Nigerian theologian Ikenna Okafor identified clericalism as a root problem that posed a "danger to synodality."

He went on to dub this a "sacerdotal megalomania," which he said is evident "when the priest is so much conscious of his power that he decides to use this power in a manner and way that does not actually lead to pastoral charity."

Too often, he said, a priest believes that his power is unable to be challenged because he is the only one that performed a certain function in his community, and "then it becomes an abuse to use this power against the community."

'No one is saved alone. In Africa, we are a family. Therefore, all of us should be engaged.'

—Fr. Nicholaus Segeja

Fr. Nicholaus Segeja of Tanzania, a member of the Vatican's Theological Commission for the synod, concurred, saying that there is often a mindset in Africa that theology only belongs to a select few — a problem he said was particularly acute in seminaries.

A constant thread in the writings of Pope Francis, said Segeja, is one of "inclusiveness."

"This has made us look at life differently," he added. "No one is saved alone. In Africa, we are a family. Therefore, all of us should be engaged."

Sengalese Sr. Anne Béatrice Faye of the Congregation of Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception of Castres pointed to Francis' 2018 Episcopalis Communio, which outlines the structure of the synod.

Faye observed that the constitution emphasizes the role of episcopal communion between the bishops and the pope, marked by mutual understanding and listening.

This, she added, should "shape how a bishop relates to his own priests and laypeople, and then gradually from the top down, we are developing a synodal community."

Mass is celebrated July 20 during the Pan-African Catholic Congress on Theology, Society and Pastoral Life in Nairobi, Kenya. (NCR photo/Christopher White)

Okafor offered a similar observation, noting that "synodality is grounded in fraternity."

"To me, synodality is not actually about structure or doctrine, but the attitude that we bring to this common journey where the priest and people march together as equals but with different functions within the community," he said.

If embraced, this could have dramatic repercussions, said Nigerian theologian SimonMary Asese Aihiokhai, who said that the hierarchical, vertical structure of the church continues to colonize — a fact that he lamented when specific reference of LGBT persons was not included in the congress' final statement.

"That is a universal problem, but Africa is suffering because Africa has refused to let go of the colonizing theology and structures given to it by the missionaries," said Aihiokhai.

'If we really want to embrace synodality, we have to see synodality as a decolonizing tool.'

—SimonMary Asese Aihiokhai

What is needed, he observed, is not just a reexamination of the priesthood, but more importantly, a reengagement of the theology of baptism, which he said emphasizes the role that all of the people of God, not just the priest, have to play in the church.

"If we embrace the rich, dynamic understanding of baptism, we can correct the abuses of the church," he said. "If we really want to embrace synodality, we have to see synodality as a decolonizing tool."

'Walking with our ancestors'

Conversations about synodality can pivot to hot-button issues, such as women deacons or married clergy, but at the congress these were often seen as second- or third-tier topics. Attendees said if the pope opens the doors for such possibilities, they would happily go along with it, but they weren't at the top of their docket or among the most pressing needs.

Instead, the most frequently discussed issues tended to be economic concerns, war and climate change.

Bishop Eduardo Hiiboro Kussala of Tombura-Yambio, South Sudan, told NCR that "synodality has an element of unity" — something that he described as especially needed in a country ravaged by a decadelong civil war.

"It's an invitation for our people to get together. In a country like mine, we use this as a method where we can bring together people that are broken apart by conflict to listen to one another," he said. "This can create a road map to bring a peaceful country."

Advertisement

He also noted that confronting corruption and the economic imbalances within society were among the top issues raised in local diocesan listening sessions, especially among youth, who make up an overwhelming majority of the African church.

"People would like to see their church active in social justice," he said.

Emilce Cuda, co-secretary of the Vatican's Pontifical Commission for Latin America and the Holy See's official representative to the congress, encouraged participants to be just that.

"Social justice is at the center of the social teaching of the church," she said. "That is not an accident."

"For some people, to speak about social justice is to not speak about theology," she observed, but the "theology of the people" demands standing with workers, the economically oppressed and those involved in popular movements.

"This is not communism," she said. "This is Christianity."

Emilce Cuda speaks at the Pan-African Catholic Congress on Theology, Society and Pastoral Life on July 19 in Nairobi, Kenya. (NCR photo/Christopher White)

Cuda was among theologians from other continents who were part of dialogue with African theologians and scholars at the congress. Also during the congress, the editorial board of the theological journal Concilium — which was founded in 1965 to promote the theology of the Second Vatican Council — met in Africa for the first time.

In addition, the congress invited ecumenical partners, including Bishop Laurie Larson Caesar of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America.

"We had to come from the Oregon Synod to Africa to be asked about what synodality looks like for Lutherans," she told NCR, describing her work in the Lutheran Church's Oregon Synod, which has gone ignored by the local Catholic hierarchy but piqued the interest of theologians in Africa. "That's a sad but true irony, but it's not a condemnation of the whole Catholic Church by any means. It's just a heartache."

Juan Carlos La Puente, who serves as Caesar's associate for intercultural and interreligious mission, said that synodality demands that the church considers questions like "With whom do we want to walk? With whom do we feel called to walk?"

But it also, he added, "means walking with our ancestors."

In Kenya, another proverb of ancestral wisdom repeated throughout the congress was "If you want to walk fast, walk alone. But if you want to walk far, walk together."

'Culture wars, at least not in the same way, are just not present here.'

—William Cavanaugh

"There seems to be a sense that that's real here," said DePaul's Cavanaugh, who observed that the congress focused on "a whole different set of issues than what the church in the U.S. is typically obsessed with."

"Culture wars, at least not in the same way, are just not present here," he told NCR.

As the conference concluded, Ugandan Sr. Mary Justine Naluggya, a canon lawyer from the Sisters of the Institute of the Immaculate Heart of Mary Reparatrix, observed that many missionaries came to Africa to "bring us the faith."

Now, she said, it was time to go out and allow those from Africa to offer an example to the rest of the church, one she said that was marked by "co-responsibility" of all of the church's members, "which drives us to synodality."

There are those, observed, Sr. Katunge, who believe that the process of synodality is over now that local listening phases are complete. And the same could be said of the congress and the weeklong discussions that took place in Nairobi.

But in the words of Katunge: "This is just the beginning."