Spencer Cullom on the Duke University campus in Durham, North Carolina (RNS/Yonat Shimron)

After finally accepting her call to preach, Spencer Cullom took a step of faith and began the yearslong process to become ordained in the United Methodist Church.

She believed God called her to become a United Methodist minister.

And she hoped that her denomination would drop its restrictions against LGBTQ clergy and allow her to follow that call.

But Cullom knew that might not happen.

"If the language in the Book of Discipline doesn't change, I will not go through with this," the 29-year old Duke Divinity School student vowed in fall 2017 when she sent a letter to a church official declaring her intention to begin the ordination process.

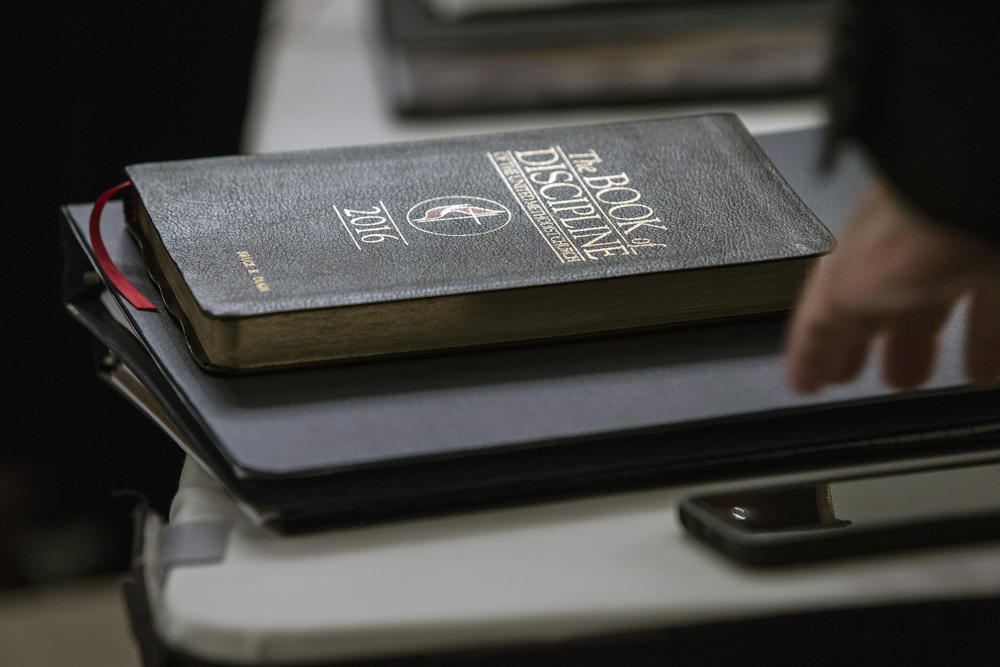

A ruddy-faced brunette with long, wavy hair and an easy smile, Cullom is a lesbian, and her denomination's rule book — called the Book of Discipline — bars "self-avowed practicing homosexuals" from being ordained. It also calls the "practice of homosexuality … incompatible with Christian teaching."

In February, the 12.6 million-member denomination decided to strengthen its LGBTQ clergy ban.

Last week, in Evanston, Illinois., the denomination's top court ruled on the constitutionality of the recent vote to strengthen the bans against LGBTQ ordination and marriage. The vote was ruled legally valid; new penalties on clergy violating the rules will go into effect Jan. 1.

A copy of the Book of Discipline rests on a table during a UMC Judicial Council meeting on May 22, 2018, in Evanston, Illinois. (Kathleen Barry/UMNS)

Few were watching the ruling as closely as LGBTQ seminary students whose calling and livelihoods are dependent on the outcome of the court's ruling.

Next month, about 200 students at United Methodist-affiliated theological schools will don cap and gown and accept a Master of Divinity diploma — required for all United Methodist ministers. A few dozen will be LGBTQ.

In the face of so much uncertainty, some of those seminary graduates will seek ordination in other denominations. They might turn to the Presbyterian Church (USA), the Episcopal Church, the United Church of Christ or the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America — groups that have amended their rules to allow LGBTQ ordination.

Others may try chaplaincy or work for religious nonprofits.

As Cullom put it bluntly: "Everybody's in chaos. I have no job, and I'm graduating in May."

Playing in the Methodist sandbox

The United Methodist Church is the only church Cullom has ever known.

Born in Charlotte, North Carolina, she was baptized at Myers Park United Methodist Church, one of the city's largest and most prominent congregations. When she was 10, her family moved to Georgia and joined St. Andrew United Methodist in Marietta.

Church played an outsized role Cullom's upbringing. She sang in the youth choir and later in the adult praise band.

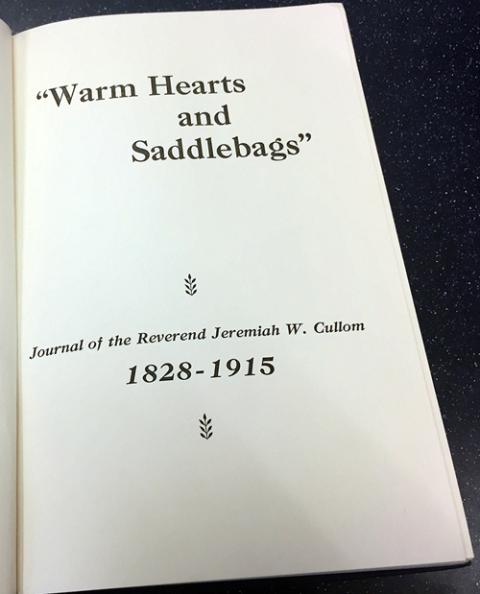

A book written by Spencer Cullom's great-great-grandfather, a Methodist circuit rider named Jeremiah Cullom. (RNS/Yonat Shimron)

She grew up knowing she had a long Methodist pedigree. Her parents and grandparents are Methodist. And she counts among her great-great-grandfathers the Rev. Jeremiah W. Cullom (1828-1915), a Methodist circuit rider from Tennessee who published a journal about his itinerant ministry called "Warm Hearts and Saddlebags."

Cullom came out as a lesbian during her senior year at LaGrange College, a United Methodist-affiliated school about 90 miles south of her home in Kennesaw, Georgia.

For a time, she was engaged to another woman, but broke it off before seminary and has not had a partner since.

"My parents were fantastic through that," she said. "They were always open and accepting and loving."

But reconciling her sexual identity with her faith was a lot harder.

She had long conversations with a campus minister to help her read the Bible through a lens of love, instead of focusing on "the clobber passages," she said, referring to those biblical verses that call homosexuality an "abomination."

After graduation, she took a job in the circulation department of Youth Today, an online publication for people who work with teens. She was still figuring out how to integrate her sexual identity and her faith when she said she heard God calling her to go to seminary.

She visited Wesley Theological Seminary in Washington, D.C., Candler School of Theology in Atlanta and Duke. At Duke Chapel she heard a sermon about how the United Methodist Church was wrong to deny some people leadership positions.

"Yes, that's 100 percent it," Cullom thought and decided she had picked the right school.

"If you don't want me in your sandbox, I don't want to be in your sandbox."

—Spencer Cullom

At the same time, she was not sure she wanted to seek ordination.

Cullom described her attitude as: "If you don't want me in your sandbox, I don't want to be in your sandbox."

She might find some other ministry job, she reasoned.

She didn't need to be ordained.

Instead, she focused on her studies and became active in Sacred Worth, a divinity school organization that strives to raise awareness and understanding of LGBTQ people in the church.

No retreat on inclusivity

Most United Methodist seminaries have become friendlier places for LGBTQ students, even as the denomination has not.

In part, that's because the seminaries are ecumenical, training students for ministry in multiple Christian denominations, not just the United Methodist Church. They offer numerous degree programs, for pastors but also for lay practitioners and for those seeking an academic career.

None of the 13 United Methodist-affiliated seminaries excludes students on the basis of sexual orientation.

Alexander Dungan, of Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary near Chicago, sits near an exit of the America's Center after a vote to adopt the Traditional Plan at the UMC General Conference Feb. 26 in St. Louis. (RNS/Kit Doyle)

At February's General Conference, a seminary spokesman read a statement warning that keeping the ban on LGBTQ ordination could drive away current and future students.

"We may very soon lose an entire generation of leadership here in the United States," the statement said.

Despite the denomination's vote, seminary leaders do not appear to be backtracking from their commitments to inclusivity.

The Rev. Jay Rundell, president of the Association of United Methodist Theological Schools, said the school he leads, Methodist Theological School in Ohio, will not back down.

"We've been very clear that we're not changing our stance on inclusiveness and our board of trustees voted unanimously to make that statement after General Conference," Rundell said.

The seminaries each receive modest but declining financial support from the denomination — on average about 10 percent of their budgets.

And while many seminary heads said their schools would suffer financially without the denomination's support, they plan to stay the course.

Some have gone a step further.

For the past decade, Candler School of Theology has run a placement service to help LGBTQ students find a geographic region where United Methodist Church boards will ordain them. If a United Methodist student fails to get ordained in Alabama, for example, the service will recommend the student to a California church region, known to circumvent church rules and ordain LGBTQ members.

"I want to maintain good relationships with conservatives," said Jan Love, dean of the Candler School of Theology and the immediate past president of the Association of United Methodist Theological Schools. "But we're going to help our students do what our students feel is God's call on their life."

A turning point

God's plan for Cullom was revealed in a fairly mundane way, she said: The pastor of the church where she was interning as part of her degree requirement asked her to deliver a sermon.

Spencer Cullom on the Duke University campus in Durham, North Carolina (RNS/Yonat Shimron)

Cullom protested.

She wasn't planning to pursue ordination.

But the pastor insisted.

So Cullom dove into the Scripture readings for that day's sermon. She started scribbling sticky notes and posting them on a whiteboard in one of the church offices. Before long, it was covered with color-coded notes and black marker arrows linking her various thoughts.

"It looked like one of those conspiracy maps where you're connecting things," Cullom said.

The experience, she said, was exhilarating — "magical and beautiful and amazing."

And then there was the delivery.

Starting with a video clip from the TV show "The West Wing" and references to the Japanese art of repairing broken pottery, called "kintsugi," she expounded on a passage from Mark's Gospel in which Jesus calls his disciples to go out and heal those who are physically or spiritually sick.

"God is the one who heals, who places people in our path who can help us, and who places us in the path of those we can help," she intoned in a clear, measured but passionate way.

The warm response from the congregation at Faithwalk, a United Methodist Church near Greensboro, North Carolina, energized her.

"It was an incredible first sermon and it was really amazing to watch her confidence as she was preaching," said the Rev. Carter Ellis, pastor of the church at the time.

For Cullom, it was a turning point.

After delivering the sermon, she realized: "This is what I'm supposed to do."

She had moved from "I won't play in your sandbox" to "Wait a minute. It's my sandbox. I'm going to play here. You can get out if you don't like it."

In her classes, she had learned about Martin Luther, John Wesley, Jarena Lee, Maria Stewart — Christians who pursued their call to preach in spite of the established church.

A few weeks later, she emailed a formal letter to the regional overseer of the denomination declaring her intention to seek ordination.

The interior of Goodson Chapel at the Duke Divinity School (Creative Commons)

A fateful decision

All along, Cullom knew the United Methodist Church was about to weigh in on LGBTQ sexuality.

She was encouraged that many United Methodist clergy and the Council of Bishops supported a plan to remove the passages restricting gay people and allowing pastors and regional bodies to make their own decisions on LGBTQ members.

As the General Conference approached, she felt hopeful but anxious.

She talked to her therapist about how to approach what she envisioned as four nerve-wracking days. The best plan, she decided, was to stay busy and find some distractions.

The first two days of the conference — Friday and Saturday — she helped emcee Broadway Revue, a musical performance the divinity school puts on to raise money for hospice.

Her parents, siblings and grandparents drove to Durham to see the show.

On Sunday, Cullom, now a member of Faithwalk United Methodist, was busy ministering to the youth group. Monday she had no classes so she arranged a watch party. Another group of Methodist students took over a classroom to watch the conference live from the convention center in St. Louis. The two groups teamed up.

That day, a church legislative committee struck down the so-called One Church Plan that would have dropped the restrictive rules regarding LGBTQ clergy and same-sex weddings.

Tuesday morning Cullom went to class and then spent the rest of the day watching as delegates approved the Traditional Plan by a vote of 438-384. That plan includes punitive measures for pastors who disobey.

United Methodist delegates who advocated for LGBTQ inclusiveness gather to protest the adoption of the Traditional Plan on Feb. 26 during the special session of the UMC General Conference in St. Louis. (RNS/Kit Doyle)

It took Cullom a week to absorb the news. She walked down Duke's gothic hallways, her eyes filled with tears. Professors and fellow students stopped to ask if she was OK.

Switching to another denomination — one that gives LGBTQ people full equality — didn't feel right. She had cast her lot with the Methodists, and she would remain one.

But she could not live with the prospect of keeping her sexuality quiet for the sake of getting ordained, or living with the knowledge that her church regards her as being "incompatible with Christian teaching."

She let her fellow LGBTQ peers know she respected their decision to pursue other avenues for ordination.

On March 5, she sat down with her laptop and composed an email.

"Due to the fact that harmful language regarding LGBT people seeking ministry remains in our Book of Discipline," she wrote to a church official, "I must respectfully withdraw from the candidacy process at this time."

Then she hit send.

Advertisement