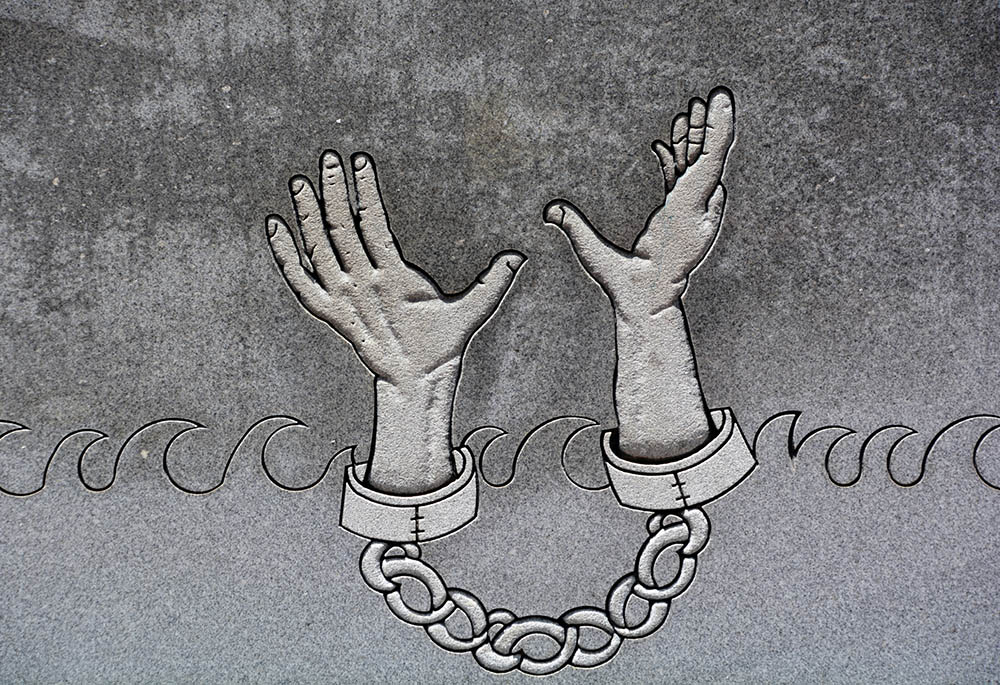

Detail of the African American Monument erected in 2002 in Savannah, Georgia (Dreamstime/Meunierd)

Amid the turmoil of the early civil rights era, James Baldwin, in a penetrating essay, asked his nephew "to imagine how you would feel if you woke up one morning to find the sun shining and all the stars ablaze."

That sense of "upheaval in the universe," he continued, was what white folks were experiencing at that moment. As the Black man who "has functioned in the white man's world as a fixed star ... moves out of his place, heaven and earth are shaken to their foundation," he wrote in The Fire Next Time.

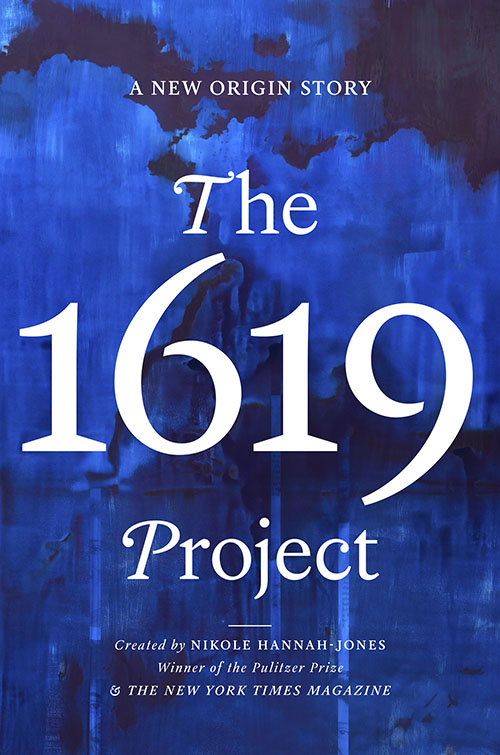

The line came to mind as I cracked open the tome The 1619 Project: A New Origin Story, the greatly expanded treatment of the original The New York Times Magazine version published in August 2019. That special edition of the magazine marked the 400th anniversary of the arrival of the White Lion, a Dutch vessel, at the British colony of Virginia. It delivered between 20 and 30 slaves from Africa, the first to arrive in what would become the United States, according to the project.

I approached the book with competing questions in mind: Is the 1619 Project so roiling some in the academy and the pundits because it is basically incorrect? Or is it because it is basically correct? Is it something in between? Could it be that the project, however flawed, represents Black men and women once more moving out of a fixed place?

I am not a historian, but a project causing such a stir over interpretation of history won't be confined to the groves of academe. And having applauded the initial magazine presentation as a proper and overdue dose of truth-telling, I couldn't ignore the book version. In short, I found the book unsettling in the way that happens when you listen differently to someone you think you know only to realize that the other is far richer in experience and complexity than you had previously imagined. It lays out a history that is too often hidden, overlooked, demeaned, underestimated and known only in fragmented ways.

There are, to be certain, overstatements in the original magazine presentation and matters of fact legitimately in dispute. While the book is the main concern here, one can't just walk past some of the disputed assertions of those pieces that linger as obstacles on the way to the deeper treatment. The details of those disputes can be found via the links listed in the accompanying sidebar.

Not conventional history

One of the most upsetting to some scholars is the assertion that the Revolutionary War was fought primarily to preserve slaveholding. Nikole Hannah-Jones, creator of the project that was awarded a Pulitzer Prize, wrote the introductory magazine essay containing the claim. She has since — and in the book version — walked that back a bit.

In the initial essay, she wrote: "Conveniently left out of our mythology [of the U.S. founding] is the fact that one of the primary reasons the colonists decided to declare their independence from Britain was because they wanted to protect the institution of slavery." In the book, she says in response to objections, "to clarify that this sentence had never been meant to imply that every single colonist shared this motivation, we changed to sentence to read 'some of the colonists.' "

In addition, she writes in the book's preface, "We wanted to learn from the discussions that surfaced after the project's publication and address the criticisms some historians offered in good faith, using them as road maps for further study."

So, the compilers of the volume modified some points, expanded on others, and added significantly to the text and literary offerings. As Hannah-Jones explains, the book, with its 493 pages of text and 65 pages of notes, does not constitute conventional history, but "combines history with journalism, criticism, and imaginative literature to show how history molds, influences and haunts us in the present" (emphasis in the original).

A letter from some historians also objects to what they perceive as the project's intent to recast American history so that "slavery and white supremacy become the dominant organizing themes." Other historians asked to sign on declined, some agreeing with elements of the critique but uncomfortable with the dismissive tone of the letter.

While applauding "all efforts to address the enduring centrality of slavery and racism to our history," the letter-signers contend that the project contained errors concerning "major events" that "cannot be described as interpretation or 'framing.' "

Jake Silverstein, editor in chief of The New York Times Magazine who approved the project, responded, disagreeing with the claim that the work contained major factual errors. He said the magazine undertook the project, in consultation with historians and based on works of history, "to address the marginalization of African-American history in the telling of our national story and examine the legacy of slavery in contemporary American life."

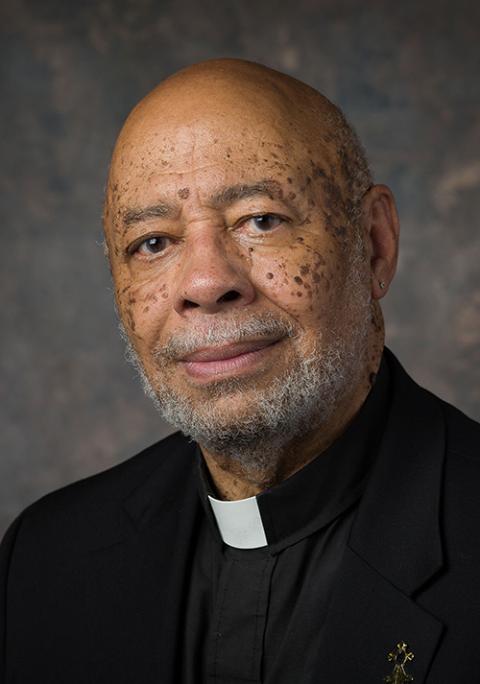

A critique of another sort was registered by a friend, Fr. Joseph Brown, a Jesuit who teaches in the School of Africana and Multicultural Studies at Southern Illinois University. In an email response to a question, he said he would go back to 1526 as the year "the massive sin of enslavement defined this country and other colonial powers." His complaint about the 1619 Project is that "the Spanish and French had as much of an impact on the enslavement of Africans as did the English — they all had colonies in what is now the United States."

Jesuit Fr. Joseph Brown (CNS/Courtesy of Joseph Brown/Steve Donisch)

I first encountered Brown in 2001, just weeks after 9/11 when I walked into a workshop he was conducting at a Call to Action conference. A Black hymn played softly in the background before he launched into an analysis of 9/11, cutting against the patriotic themes of the moment. He said that he wasn't surprised by the attack.

It wasn't exactly a Rev. Jeremiah Wright "God damn America" moment, but it was a jolt to the prevailing sensibilities. Because, Brown said at the time, he taught a lot of Black young men who understood the demands of a violent culture that viewed them as a threat. Further, he said, he knew the history of Black oppression that was probably unfamiliar to the white audience crammed into the small workshop space.

In an email recalling that instance, he repeated phrases he used to explain himself: "If I have to know, you have to know," and "If I'm not exempt, you're not exempt."

"A country that employed the strategies of terrorism, domestically and internationally, couldn't pretend to an innocence that was obscene," he wrote in the email. "And yet ... that is what happened, and that is what is happening all over again — or, still — today."

In presenting that workshop, he said, "I knew about lynchings. I knew about the insidious and toxic control of those who used the KKK and other supremacist movements to suppress or even erase the Black and Indigenous populations in this country. I knew that they knew. The laws of suppression and erasure proved that they knew what they were doing. The vigilantes who were condoned by the Second Amendment — and to this day, still are — were conscious and intentional in killing every 'threat' to their power and false complacency."

Brown was not a one-off. There were a lot of people who knew the 1619 narrative long before The New York Times project.

A deeper foundation

If the civil rights era shook the foundation, the 1619 Project is suggesting that the culture needs to dig further, to another level, to discover an even deeper foundation.

Pointing to 1619 as a founding moment is not as repulsive to me as it is to some. I can't conceive that acknowledging and elevating a formative element of what became U.S. culture would negate the formal founding of the republic. Nor can placing that date front and center overwhelm the founding documents and strip them and the founders of some of the noblest intentions to be incorporated in any materials establishing a nation state.

Philadelphia, June 2020 (Unsplash/Chris Henry)

That last point seems especially the case, given the number of times in the book version that the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution are invoked by Black historic and contemporary figures as the rationale for continuing to fight for civil rights.

The essay by Carol Anderson, who teaches African American studies at Emory University, outlines the underlying tensions from the start of the republic.

During the 1787 Constitutional Convention, she writes, James Madison "recognized that though all the delegates were determined to create a viable nation, there were two divergent agendas under the surface. The Deep South was intent on strengthening the slaveholders' power and protecting the institution of slavery. Meanwhile, other delegates were motivated by a variety of moral, economic, and philosophical reasons. The asymmetry allowed the dream of the United States of America to be held hostage to the tyrannical aims of enslavers."

The struggle since has been to release the dream, bit by bit. That somehow the founding principles, the origin of the dream, would be defiled by the 1619 Project is contradicted by the fact that Hannah-Jones' explicit hope for the future, in quite literally her final analysis, rests unqualifiedly on "the magnificent ideals upon which we were founded."

From the scholars' complaints about errors of commission to Brown's complaint about errors of omission, it might be best to simply admit there is no perfect 1619 Project.

There is, however, far too much of substance here to disqualify it as the debate proceeds. I think the work will endure as a compendium of a shadow stream of U.S. history through the eyes of those who lived it, who are the inheritors of it, who to this day understand, more clearly than anyone without dark skin can, the lasting effects of it.

In the book, Hannah-Jones lists questions at the heart of the project, and the first is one that I found most striking: "What would it mean to reframe our understanding of U.S. history by considering 1619 as our country's origin point, the birth of our defining contradictions, the seed of so much of what has made us unique?"

I find the question far more provocative and motivating than objectionable. Certainly, it requires accepting that race and slavery, as they have occurred in the U.S. context, are peculiar to us and perhaps unique in their scope and longevity.

Nikole Hannah-Jones (Wikimedia Commons/Abraji/Alice Vergueiro)

The question for me provokes reflection, first, in a personal way on very basic realities that still are part of U.S. culture. I know that the presumptions that are packed into my understanding of how I will be perceived in countless situations and what I can take for granted day to day are not the same for my Black neighbors down the hall or in units above and below me in the condominium building where I live.

In the larger context the question arises: Where does it all fit? It seems inevitable that to give the history of enslavement and its far-reaching effects a proper place in how we understand the United States will require deconstructing some of the long-accepted images to make space for long-ignored truths.

Or as Brown put it, "The voiceless will sing until you are forced to hear them. From the beginning of European settlement, we have the songs, we have the rebellions of the enslaved; we have sermons and letters and autobiographical challenges to the dominant narrative."

A new awareness

An unfortunate side effect of the 1619 Project is not the disputed facts or interpretations but that the debate, at least in the case of the book, distracts from a valuable compilation of history, data and art. It is a work that pulls together in an accessible way strands of a largely hidden or ignored history that at best gets treated in a cursory manner in the normal course of a U.S. education. Even many critics agree with that assessment.

The irony is that perhaps not since the intense awareness that much of the white population experienced during the civil rights era has there been another time that the culture was so focused on the issue of racial inequality.

Advertisement

In that previous era, thanks to Black Americans' courage, and to demonstrations, sit-ins and marches that attracted coverage, white America was treated via the evening news to an unprecedented exposure to the simple demands and sometimes horrific treatment of Black Americans.

Today, the smartphone camera has become an instrument of justice, exposing the raw truth of police brutality and murder and moving millions to organize anew to counteract white supremacists and racially motivated laws.

It is as if we're living through this prolonged period of cultural self-disclosure. We can be good enough to elect a Black man, a constitutional law scholar, to two terms as president that he serves without hint of scandal. We can be derelict enough to elect a marketing sorcerer without a hint of governing experience who plays to our worst racist elements and who has utter disregard for constitutional norms and democratic institutions.

We can witness in the 2020 presidential election "the highest voter turnout of the 21st century, with 66.8% of citizens 18 years and older voting," according to the U.S. Census Bureau. And follow that with a spate of voting suppression laws aimed at disenfranchising minorities, especially Black voters, and poor urban populations.

In the large social context, things can at times seem as promising as President Barack Obama's farewell address in 2017, when he declared American exceptionalism did not mean "that our nation has been flawless from the start, but that we have shown the capacity to change and make life better for those who follow."

In that personal instance, it might seem a bizarre declaration given the chaos and incompetence that followed him into the White House. In a much broader way, however, Ibram X. Kendi argues in the 1619 book that Obama "became" the version of "an American history popularly written as the story of incremental and steady racial progress."

Ibram X. Kendi (Wikimedia Commons/Montclair Film)

It is a version that Kendi, director of the Center for Antiracist Research at Boston University, once believed but has since abandoned. In one of the more sobering essays in the book, Kendi writes he has come to understand that the hope depicted in the familiar expression, "The arc of the moral universe bends toward justice," is an incomplete expression of the experience of Black America.

"The long sweep of America has been defined by two forward motions: one force widening the embrace of Black Americans and another force maintaining or widening their exclusion," he writes. "The duel between these two forces represents the duel at the heart of America's racial history. The myth of singular racial progress veils this conflict" as well as the effects of racism so evident today.

In his letter to his nephew, Baldwin turns the tables on usual assumptions. "Please try to remember that what they [white people] believe, as well as what they do and cause you to endure, does not testify to your inferiority but to their inhumanity and fear."

Yet Baldwin counsels: "The really terrible thing, old buddy, is that you must accept them. And I mean that very seriously. You must accept them and accept them with love. For these innocent people have no other hope. They are, in effect, still trapped in a history which they do not understand; and until they understand it, they cannot be released from it."

In the end, whatever flaws one might find in the 1619 Project are, in reality, less disturbing than the fact that the project shines light on the inadequacies of the established narrative. The 1619 Project finds the loose threads in the tapestry and pulls at them in a way that starts to undo the faulty picture of the past with which we've become comfortable, in order to make room for a more complete view of the past. It is a valuable segment in the long journey toward understanding a history from which we might ultimately be released.