We know by now (or should if we are paying attention) that the Black American experience is not a monolith. (BlackIllustrations.com)

We know by now (or should if we are paying attention) that the Black American experience is not a monolith. Though there are some overarching themes, our individual experience varies widely and has ever since the first Africans were kidnapped and taken to America in 1619.

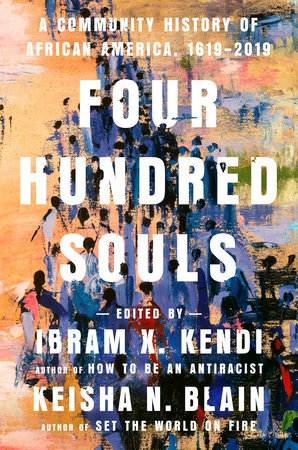

Four Hundred Souls, edited by Ibram X. Kendi (author of How to Be an Antiracist) and Keisha N. Blain (author of Set the World on Fire), presents a new way to engage Black American history. It is a community history of Black America, a story told by the people inhabiting it — a "for us by us" endeavor, conceived out of the premise that, as Kendi puts it, "solidarity is the womb of community."

Eighty Black writers and 10 Black poets participated in the venture, with each writer covering a specific five years in history and poems punctuating each of the 10 sections of the book. We read about Black American history from a group as diverse and unique as our ancestors themselves. Their voices are a choir, the poems rising like solos, a hymn to Black American life.

Catholics should find the universality of the work familiar. What better analogy for the individual people, countries and cultures brought together in the body of Christ than a choir, brought together in glorifying song? Themes of death and rebirth, struggle and solidarity, community and diversity are part of the history of Black America, just as in the history of the Catholic Church.

Faith is a consistent anchor point throughout Black American history, and Black Catholics are not absent from Four Hundred Souls. One chapter tells the story of Anthony Johnson, a Black Catholic in Virginia. Born in Africa and kidnapped into slavery, Johnson bought his freedom and that of his wife Mary and eventually became a slaveowner. We learn how enslaved people escaped the British colonies, where profit motive meant that Christian baptism was no longer a sufficient moral reason to free a slave, to Spanish Florida, where professing the Catholic faith could earn them their freedom.

Four Hundred Souls approaches the telling of Black American history as a communal project. Because each chapter is told in its contributor's voice, reading the book is less like reading a history textbook and more like sitting on the porch listening to family members talk about their memories and lived experiences.

Advertisement

Each chapter tells its own story, and the collective stories paint a vivid historical portrait.

Through narrative, essay, memoir and poem, they bring us from "1619-1624: Arrival" — written by Nikole Hannah-Jones, the Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and creator of "The 1619 Project," to "2014-2019: Black Lives Matter" by Alicia Garza, co-founder of the Black Lives Matter movement. There is so much in between.

Ijeoma Oluo explores how the early enslavers' worries about miscegenation became the foundation for a legal and social framework under which we still, to an extent, operate today. We learn from Brenda Stevenson how the early denial of Black women's femininity still resonates in today's world. The legal, social and religious structures created and perpetuated to ensure continued white social and political supremacy in America are explored throughout the book, in the Rev. Dr. William J. Barber II's chapter on David George, Deirdre Cooper Owens' chapter on the Fugitive Slave Act, John A. Powell's chapter, "1854-1859: Dred Scott," Howard Bryant's chapter on boxer Jack Johnson, Chad Williams' chapter on the Black soldier, Esther Armah's 1999-2004 chapter on the Black immigrant and myriad others.

Harriet Tubman, abolitionist (BlackIllustrations.com)

Four Hundred Souls covers slave codes in Virginia, slave revolts in New York, the Louisiana Rebellion, the Albany 3, Atlanta, Philadelphia, the Great Migration, and the Harlem Renaissance. The book dispels the notion that Black Americans only exist in certain parts of the country and the equally pervasive myth that Black Americans were only ever seriously mistreated in the South.

I recommend Four Hundred Souls to anyone interested in learning more about Black American history, specifically from Black Americans. The book will also inform anyone whose formal education skipped from "slavery, which was bad," to "the civil rights movement, which was good" with little exploration of either and no word on what Black Americans were doing from 1865 to 1965. Even those with a solid knowledge of Black American history will find the book refreshing and informative.

For Catholics interested in learning about Black American history, whether to confront the sin of racism or lift the voices of those long ignored, Four Hundred Souls illustrates how the present is shaped and informed by the past and provides endless jumping-off points for further reading. From the Black Codes to the Combahee River Collective; spirituals to hip-hop; Phillis Wheatley to Zora Neale Hurston; Four Hundred Souls confirms that Black people have always been in America, have always been part of American history and will be part of America's future.