"The Last Communion of Saint Mary of Egypt," a 1680 painting by Marcantonio Franceschini (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

In Naples, Rome and Jerusalem there are churches and chapels dedicated to a saint unknown to most of us and whose historical existence lacks actual evidence despite ample devotion among early Byzantine, Orthodox, Coptic and Roman believers. Now two contemporary authors are exploring the story of St. Mary of Egypt, patron of penitence.

Tradition holds that at age 12, Mary left her rural home along the Nile and went to the flesh pots of Alexandria where she lived for 17 years working as a prostitute not for financial security, but for pleasure. One day, she boarded a ship bound for Jerusalem where she visited the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, but a powerful force kept her from entering. There she is said to have prayed for forgiveness before an icon of the Virgin Mary and when she was finally allowed to enter, she venerated the holy cross. There a voice commanded her to cross the Jordan River, assuring her that there in the desert she would find peace.

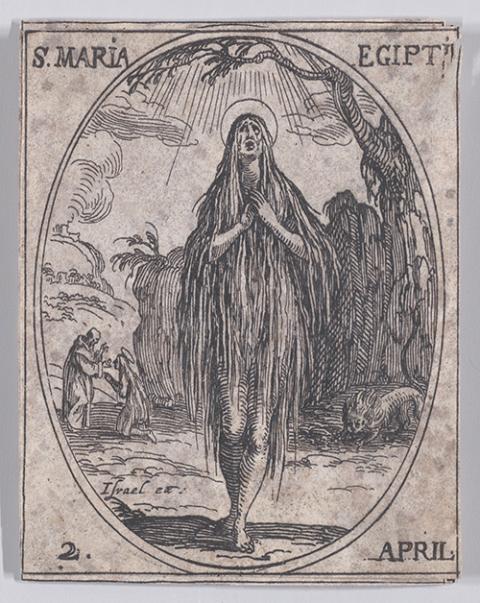

For years Mary lived naked in the desert wilderness doing penance. Near the end of her life, a monk named Zossima (also known as Zosimas or Zosimus) also went to the desert and there encountered Mary, to whom he gave his mantle to cover herself. Mary told him her story and he recognized her as an incarnation of humility. When he returned a year later, Zossima gave her the Eucharist and saw her walk on water and levitate. The next time he returned, he found Mary dead, her body uncorrupted, and buried her with the help of a desert lion. In the seventh century what had been oral tradition of these dual stories of harlot and monk were recorded by St. Sophronius, patriarch of Jerusalem, as the universal story of penance and forgiveness.

"S. Marie Egyptienne (St. Mary of Egypt), April 2nd," from "Les Images De Tous Les Saincts et Saintes de L'Année (Images of All of the Saints and Religious Events of the Year)," a 1636 print by Jacques Callot (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

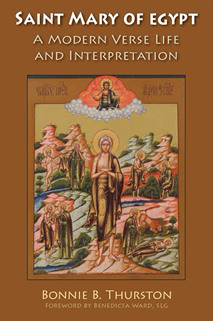

In Saint Mary of Egypt: A Modern Verse Life and Interpretation, author Bonnie Thurston details Mary's narrative and then writes a series of poems in the voices of Mary of Egypt, Zossima, the Virgin Mary and the desert lion, in order to help the reader reflect on the story's eternal truth.

In the voice of Mary she writes: "The only body I wanted / was a live and lively one" and "At its center, / my insatiable center, / was luscious fruit, / carnal knowledge/ of good and evil. / I offered the choice / to all comers, / Laughed, then moaned / as they put their hungry / hands to the plow."

The desert lion adds its voice: "I watched them meet, / the pompous old priest, / the wizened old woman. / Her I cared for. / She chose our desert, persevered here, / flourished in her way, / came to love ours. / Even the snakes / leave her alone."

But Thurston's book is not just poetry. Saint Mary of Egypt also contains exegesis tracking centuries of scholarship about the elusive Mary; scholarship that is affirmed in the foreword by the late Sr. Benedicta Ward, historian of early desert Christian spirituality. In Thurston's view, Mary is a woman of autonomy who made her own way in the world and whose conversion took place outside the structure of the institutional church; after all, it is the Virgin Mary and not a priest who first receives her repentance. Yet the author also argues for a symbiotic relationship within the respective reconciliations of Mary and Zossima: Mary needs the monk to bring her the Eucharist, and the monk needs the embodied humility of the repentant Mary. Their former sins are transformed by a gracious God: Mary, forgiven of the sins of the flesh and Zossima, of the sins of the spirit.

Advertisement

Meanwhile in the travelogue Wild Woman: A Footnote, the Desert, and My Quest for an Elusive Saint, author Amy Frykholm takes a more personal approach to exploring the mysterious Mary of Egypt, whom she calls an "icon of desire." Frykholm sets out to discover the saint's life narrative by physically embarking on Mary's path through the Nile, Alexandria, Jerusalem and the desert, including stops at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre and the Monastery of St. Gerasimos along the Jordan River. Blending her own quest for transformation with that of her subject, the author deftly weaves memoir and hagiography to create a compelling read. For Frykholm, Mary is both a woman wild with desire and an ascetic who goes to the desert to find peace, wholeness and transformation.

These two books should be read in tandem. Through different methods — poetry and travel — they provide access to a figure shrouded in mystery and ask questions about the power of legend, both works establishing desire and conversion as important aspects of the Christian tradition of holiness.

The centurieslong popularity of Mary of Egypt's life narrative points to the most foundational aspects of the Christian imagination: sin is pervasive, desire is central to holiness and the mercy of God is universal. Not bad reminders for the contemporary reader.