A mural in Belfast, Ireland, commemorates the Great Hunger of 1847-49. (Wikimedia Commons/Keith Ruffles)

Last year, The New York Times published an essay titled "Why We Will Need Walt Whitman in 2020." Author Ed Simon lamented the dark, nationalistic chants echoing across America, and, as an antidote, proposed a generous dose of Whitman's more democratic, barbaric yawp.

"A demagogue may whip his admirers into a hateful frenzy and impart the illusion of unity, but the loving work of democracy actually provides that unity," writes Simon.

Simon isn't the first person to offer up Whitman as a bard of harmony, though it's also worth revisiting what Whitman said when, as a budding journalist, he stumbled upon a rather unharmonious scene, a street fight in Brooklyn.

"We saw Irish priests there — sly, false, deceitful villains — looking on and evidently encouraging the gang who created the tumult," Whitman wrote, adding that the immigrant combatants were "bands of filthy wretches ... drunken loafers ... disgusting objects ... these were they who broke into the midst of a peaceful body of American citizens."

Do I contradict myself, indeed!

Whitman would later atone for such youthful indiscretions. Still, the juxtaposition of the Whitman myth and his actual words reveals important things about the great poet's time and our own.

It was only after Whitman aired these fierce anti-immigrant views, quite common among respectable American Protestants, that a staggering calamity befell Ireland's "filthy wretches." An gorta mor. The great hunger.

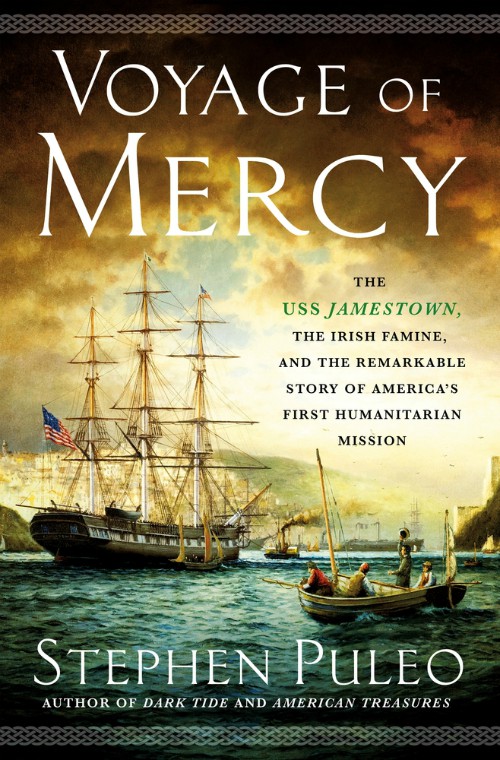

This is where Stephen Puleo's inspiring and timely story begins. He explores in laudable detail the charitable efforts Americans — rural and urban, immigrant and native-born, Christian, Quaker and Jewish — put forth to alleviate suffering brought on by starvation in Ireland.

"Prior to 1847," Puelo writes, "the bulk of interaction between nation states consisted mainly of warfare and other hostilities, mixed with occasional trade; the entire concept of international charity existed neither in the moral consciousness nor as part of the political strategy of monarchs or elected leaders."

At the center of Puleo's book are two colorful figures. Fr. Theobald Mathew was born into a wealthy Tipperary family in 1790, yet later was "gratefully embraced by Irish peasants" for his work on behalf of the poor, especially during the famine.

Then there is the lesser-known Capt. Robert Bennet Forbes. Born in 1804 in Boston, Forbes was a world traveler and wealthy trader before he turned 30. But tragedy loomed. Forbes and his wife lost "two infants in the first thirty months of their marriage." Puleo's reading of "hundreds of [their] letters" suggests that "vast distances and the rawness of great tragedy brought Robert Bennet and Rose Forbes closer together."

Advertisement

So much so that Forbes looked forward to a relatively youthful retirement. But when reports of deprivation in Ireland swept across America, Forbes, like many others, was moved to action. They believed "God had bestowed great abundance and blessings upon the United States that should be shared with the less fortunate."

Details of the famine grew bleakest in the year that would come to be called "Black '47."

"Relief committees were quickly established in key cities," Puleo writes, including Boston, where giants of the American literary scene — Thoreau, Emerson, Hawthorne, Melville, Alcott, Dickinson — "all gave voice to Boston's Irish relief efforts."

Here, as Puleo knows well, is where things get knotty. He outlines the unique threat Irish Catholic immigrants represented to "Puritan Boston," where Irish immigrants "were aliens in every sense."

How, then, to explain the charitable outpouring?

Puleo speculates it was "partly due to the guilt felt by Boston's literati and intellectual core about the mistreatment of Irish immigrants who had already arrived in Boston."

This, however, sidesteps why these thoughtful Christians were so comfortable wielding Whitman-esque condemnations of Irish Catholics in the first place.

Puleo doesn't sufficiently explore 19th-century Protestant-Catholic conflicts, and the confluence of forces — from disease and urban disorder, to poverty and political realignment — that made the famine era so contentious. And he never adequately explains why Protestant America was willing, if only briefly, to come to Ireland's aid.

Nevertheless, Voyage of Mercy tells an inspiring and resonant story.

Too often, these days, it can seem that only narratives of oppression and misery are worth telling. We lose sight of the fact that attempting to alleviate the suffering of millions, as Forbes and many others did, is a noble thing. Such charitable acts, then and now, may not upend structural deficiencies. But they are worthy of celebration just the same.

One reason inequality today seems to thrust us into an endless cycle of outrage and revolt is because too many people on all sides have convinced themselves that whatever fresh outrage dominates Twitter on a given day is not only apocalyptic, but unprecedented.

As Voyage of Mercy suggests (though could have done more strongly), a flood of suffering and impoverished refugees crossing our borders, transforming our cities, and lambasted as "an intolerable burden to the taxpayer" may be more of an American rule than exception.

None of which changes the fact that what Robert Bennet Forbes did, and as so many aid workers around the world continue to do today, fed the hungry, comforted the afflicted, and was, above all, deeply Christian.

[Tom Deignan, a regular contributor to National Catholic Reporter, has also written about books for The New York Times and The Washington Post.]

Editor's note: Love books? Sign up for NCR's Book Club list and we'll email you new book reviews every week.