A girl releases paper lanterns on the Motoyasu River facing the gutted Atomic Bomb Dome in Hiroshima, Japan, August 6, 2018, to commemorate the 73rd anniversary of the world's first use of an atomic bomb in war. More than 75,000 people were killed in Hiroshima when the United States dropped the bomb near the end of World War II. (CNS photo/ Reuters/Francis Mascarenhas)

As Hiroshima and Nagasaki commemorate loss of life and devastation of their cities Aug. 6 and Aug. 9, I find Trappist Fr. Thomas Merton's chilling anti-poem, "Original Child Bomb," worth re-reading in light of Gospel nonviolence and the chaos of the Trump era (listen to a narration or read it).

"Original Child" refers to the name the Japanese gave the atomic bomb. Merton's sardonic subtitle invites "Points for meditation to be scratched on the walls of a cave," as the Original Child blew us back to pre-human times. As I meditate on Merton's etchings on the walls of a cave, I am struck by three points that call us to face violence in ourselves (the anti-poem is divided into 41 sections).

First, by writing in a cold, bureaucratic, detached, yet reverent tone, Merton held a mirror to America. "Original Child Bomb" recites facts and the deliberate steps that political leaders, generals and scientists took leading up to and during the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Although Japanese leaders were seeking a negotiated end to the war, their overtures were rejected by the United States.

These leaders were rationally following the "logic of events." They thought that dropping the atomic bomb was the most merciful way of ending World War II and, perhaps, ending all wars forever. In section seven Merton declares "Lucky Hiroshima! What others had experienced over four years would happen in a single day! Much time would be saved, and 'time is money!' " The people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki had no say in their fate.

Recall, too, on the cusp of World War I, in his essay "The War to End All Wars," H.G. Wells wrote that "It is a war to exorcise a world-madness and end an age … For this is now a war for peace."

Despite the best intentions of military and political leaders, to the contrary, use of the Original Child ultimately prepared the way for more violence and possibly the destruction of the world. Violence begins with the hubris that our good intentions can control the use of force.

Second, "Original Child Bomb," rehearses the religious faith and reverence that leaders had for destructive violence.

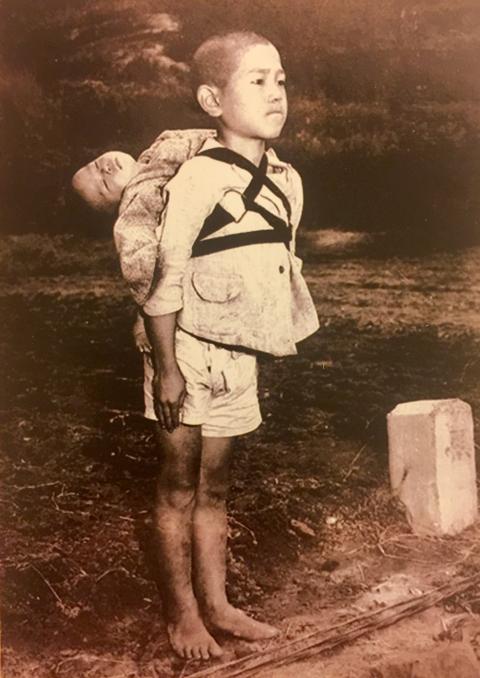

This 1945 photo taken after the atomic bombing in Nagasaki, Japan, was released December 30, 2017, by Pope Francis. The photo by U.S. Marine Joseph Roger O'Donnell shows a boy carrying his dead brother on his back as he waits his brother's turn to be cremated. (CNS photo/Joseph Roger O'Donnell via Holy See Press Office)

Upon the successful detonation of a plutonium bomb on July 16, 1945, in Alamogordo, New Mexico, Merton cites a semi-official report of the event that quoted the New Testament. " 'Lord, I believe, help thou my unbelief.' There was an atmosphere of devotion. It was a great act of faith."

As the bomb was being "assembled in an air-conditioned hut on Tinian," records Merton, the bomb's handlers named it "Little Boy." He ends section 22: "Their care for the Original Child was devoted and tender."

Indeed, as a people, as a nation, our worship for our military might and weapons has only deepened over the seven decades since we dropped the Original Child. As former Defense Secretary James Mattis stated earlier this year, "we are all aware in this country of the President's affection and support for our military."

Our own affection is expressed not only in fireworks on Independence Day and in military air shows but also in regular spending increases for nuclear and other weapons programs.

Third, Merton's anti-poem implicitly warns that the tragedy of our time is not the malice of war criminals as much as it is our own propensity to become war criminals ourselves. He makes this warning explicit in many essays including "War and the Crisis of Language."

Perhaps President Donald Trump's love for military dictators reflects more about who we are as a nation than we are willing to admit. We seem to have forgotten our national history of genocide of First Peoples, of slavery, of unending racial terror against peoples of color.

Despite claims to the contrary, we must face our long history of our national faith in violence.

Lost in the chaos and confusion of the Trump era, amidst explicit fomenting of racial violence against congressional representatives and their cities, is the fact that the world is, perhaps, at greater risk of nuclear war and terrorism.

Advertisement

Indeed, lost in the news of this past month is the fact that the United States formally confirmed its withdrawal from the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF) that was signed by President Ronald Reagan and Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev in December 1987.

In its 2019 Doomsday Clock statement that it is "two minutes to midnight," the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists warns "of the devolving state of nuclear and climate security" because of "a qualitative change in information warfare and a steady misrepresentation of fact that is undermining confidence in political structures and scientific inquiry."

While apocalypticism is dangerous — there are strains of evangelical Christianity that are explicitly inviting such violence — we are in a qualitatively different space and time that calls for a renewal of a depth of Christian adherence to truth, what Gandhi called Satyagraha.

Satyagraha begins with a deep sense of our own need to fast from violence in ourselves and our nation. That means orienting our entire way of life and being to oppressed peoples everywhere and to God. Pax Christi International's Catholic Nonviolence Initiative offers such an opportunity to pray, fast and prepare for a life of nonviolence and civil disobedience.

Now, more than ever, as the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki commemorate the loss of life and devastation of their cities Aug. 6 and Aug. 9, it is vital for people of faith and justice to join the president of the Catholic Bishops' Conference of Japan in his call for Ten Days of Prayer for Peace (Aug. 6-15). Renewing Pope John Paul II's Hiroshima Peace Appeal of 1981, Mitsuaki Takami, Archbishop of Nagasaki, invites us to "build peace by being deeply involved in the integral development of all while seeking the realization of the abolition of nuclear weapons."

Perhaps this is how we can begin to hear and honor the voices of survivors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki who call for a commitment to nonviolence and the abolition of nuclear weapons.

[Alex Mikulich is a Catholic social ethicist.]

Editor's note: We can send you an email notice every time a Decolonizing Faith and Society column is posted to NCRonline.org so you won't miss it. Go to this page, enter your address and check the boxes for the ones you want: Newsletter sign-up.