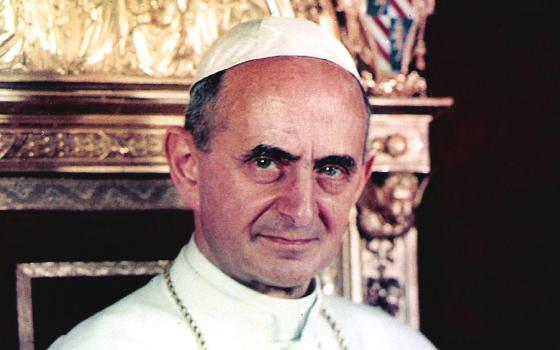

A banner referencing "Humanae Vitae," the 1968 encyclical of Pope Paul VI, is seen in the crowd at the conclusion of his beatification Mass Oct. 19, 2014. (CNS /Paul Haring)

Amidst all the criticism of Humanae Vitae on this its 50th anniversary, I should like to praise the encyclical today. It was reduced to "Pope Bans Pill" the second it was issued, but the text is actually a powerful reflection on the dangers to human life, not life as a biological fact but as a theological and anthropological fact, posed by the lingering Malthusian temptation to view human life as one more thing over which we, the powerful and enlightened, should exert mastery.

First, the caveats. Had I been on the commission that studied the issue of artificial birth control and that recommended allowing its use under certain circumstances, I hope I would have listened to all the evidence and arguments, but I suspect I would have voted with the majority. I admit this is an anachronistic judgment: I was 6 years old in 1968, and the decision was made amidst wider concerns about ecclesial authority.

Second, Humanae Vitae was the product of neo-scholastic theology; indeed, it may be seen as the last gasp of that theology. In his just issued book, The Structure of Theological Revolutions, Jesuit Fr. Mark Massa writes:

The year 1968 is offered as the starting point for the narrative that follows because that was when, in the United States, the unquestioned dominance of the specific type of natural law discourse (neo-scholasticism) that had defined Catholic moral theology for generations came to a dramatic end with unnerving specificity. And by "unnerving specificity" I simply mean that we can date the dramatic demise of that dominant form of natural law discourse to a very specific date in Catholic history: July 25, 1968.

Even Joseph Ratzinger acknowledged that he had trouble with the text because of its reliance on neo-scholasticism, although not with its conclusion.

Finally, I wish Pope Paul VI had stuck with the traditional teaching, which insisted that marriage be procreative but did not specify that each conjugal act be open to procreation. Just as we want to avoid a Gnostic dualism, we also want to avoid a biological reductionism, and I think this insistence on each marital act suffers from such a dismissal of additional and important contextual realities. This hyper-teleological understanding of a biological act does not correspond to how humans live.

Nonetheless, the main concern of the encyclical was "man's stupendous progress in the domination and rational organization of the forces of nature to the point that he is endeavoring to extend this control over every aspect of his own life — over his body, over his mind and emotions, over his social life, and even over the laws that regulate the transmission of life" (#2). He looked back to the hateful Malthusian belief in regulating society based on scarcity, a belief that had led to social Darwinism and eugenics, and forward to potential developments that would transform human life from a gift to a product.

I need not rehearse the horrors of Malthus, which have been a staple of this column since its inception, but let me recall the degree to which some people — unsurprisingly, powerful and affluent people — are already treating human life as a commodity. This article by Melinda Henneberger about searching for sperm donors is enough to make you realize that Paul VI was not delusional in his worry.

Advertisement

Michael Sandel, in his book The Case Against Perfectionism: Ethics in the Age of Genetic Engineering, sounds a lot like Papa Montini when he writes:

Breakthroughs in genetics present us with a promise and a predicament. The promise is that we may soon be able to treat and prevent a host of debilitating diseases. The predicament is that our newfound genetic knowledge may also enable us to manipulate our own nature — to enhance our muscles, memories, and moods; to choose the sex, height, and other genetic traits of our children; to make ourselves "better than well." When science moves faster than moral understanding, as it does today, men and women struggle to articulate their unease. In liberal societies they reach first for the language of autonomy, fairness, and individual rights. But this part of our moral vocabulary is ill equipped to address the hardest questions posed by genetic engineering. The genomic revolution has induced a kind of moral vertigo.

Moral vertigo is perhaps a phrase for the ages, but it is most certainly a phrase for our age. I submit that even if you think Humanae Vitae got it wrong about the pill, it was prescient about much else.

Theologian Holly Taylor Coolman touched on this aspect of Humanae Vitae as well in her recent and excellent essay at America. Confronting the myth of the self-made man, and how a Christian must, instead, exhibit a certain "preference for the given," she concludes, "From 1968 to now, and as we move deeper into Tomorrowland, whether we consider our children or ourselves, we do best when we, too, find our voices and learn to speak boldly. And we speak most boldly when beneath all our words is the affirmation: 'We have not made ourselves.' "

The other thing about Humanae Vitae is that if Paul VI had refrained from loosening the teaching for fear of undermining papal authority, his encyclical had the exact opposite effect. And, amidst the backlash, as is often the case, many of the critics and the champions of the teaching both failed to do themselves proud. For some conservatives, use of the birth control pill went from a close neo-scholastic call to the "gateway drug to the culture of death." And for some liberals, the desire to overturn one moral norm led to an essentially libertarian view of human sexuality: Anything goes so long as you don't hurt someone (unless that someone is a not-yet-born human); gender is entirely socially constructed; no moral or legal rules can impinge on human choice. When there is a group called "Catholics for Choice," a group that refuses to even acknowledge the fact that whatever else it is, an abortion is a violent act, well the intellectual and moral chaos is pretty profound.

In the book God at the Ritz: Attraction to Infinity, the late Monsignor Lorenzo Albacete insisted that the church's teaching on sexuality is linked of necessity to its teaching on the human body. "Let me … put it this way, whoever believes the human body somehow survives death should have an astounding view of sexuality!" he wrote. "It seems to me that the 'credibility' of the Christian view of sex should be tested at its deepest roots — that is, how does the church view the human body? What we have to decide is this: how important is the body in our experience of being a human person, a unique and unrepeatable 'someone'?" Albacete was worried about the latent Gnostic tendency to diminish the significance of physicality and matter, including the human body, a tendency that always ends in ruinous esoteric spirituality. We Catholics affirm every Sunday in the Creed that we believe in the resurrection of the body. We confess an incarnate Savior. We believe God created humankind male and female. These theological claims have significance.

A tapestry of Pope Paul VI hangs from the facade of St. Peter's Basilica during his beatification Mass celebrated by Pope Francis in St. Peter's Square at the Vatican Oct. 19, 2014. (CNS/Paul Haring)

God also created humankind with an ability to reflect on its own experience. Two of the best critics of Humanae Vitae, Michael Lawler and Todd Salzman, both of Creighton University, did a fine job explaining the role of experience in formulating traditional Catholic ethics. If Paul VI thought he could issue a, dare we say it, prophylactic ban on birth control before its use became widespread, he was mistaken and the church cannot ignore what we have learned about birth control since the '60s. Some conservatives argue tendentiously that if everyone had simply listened to Paul VI, the sexual revolution could have been averted. It couldn't and, besides, parts of the sexual revolution such as the opening of all spheres of human activity to women and bringing gays and lesbians out of the closet are achievements, not regrets. On the other hand, many liberals tend to ignore the cost of family breakdown in the past 50 years, the relationship of the sexual revolution to that breakdown, and the fact that the cost is paid by poor people.

Still, on this 50th anniversary, get past the headline "Pope Bans Pill" and reflect on the actual text of Humanae Vitae. See how the ban on artificial birth control, in Paul VI's eyes, dovetailed with his larger concern about human procreation changing in ways that turned human life from a gift to a commodity. Ask yourself if that larger concern is not justified, even if you disagree with the ruling on birth control. Paul VI may have been wrong, and I can only accept the teaching, as I can only accept the teaching on papal infallibility, on the authority of the church. And when the teaching develops, and it will, my confidence in the teaching authority of the church will be confirmed, not diminished. The fact that the church lives in history and teaches in real time is no cause for doubt. It is instead a cause to thank God, literally, for having interested himself in human affairs and becoming incarnate in his Son and present to the church he founded.

[Michael Sean Winters covers the nexus of religion and politics for NCR.]

Editor's note: Don't miss out on Michael Sean Winters' latest: Sign up to receive free newsletters and we'll notify you when he publishes new Distinctly Catholic columns.