(Steven Salido Fisher)

The story of La Virgen de Guadalupe as I know it begins at my abuela's bedside.

"Reza a la Virgencita para que te proteja," she would say as she pointed to the portrait hung above the headboard of her bed in her Mexico City home.

This Virgin is no blue-eyed and pale-faced Mary swaddling a baby. She is a princesa Nahuatl. Handsome. Pregnant. Her cloak, cerulean and star-studded with the night sky, envelops her body with folds cascading onto a crescent moon held by an angel.

At the end of the day, with the company of my sister and brother, our abuela lulled us into the mysteries of the rosary under La Virgen's gaze. As my siblings hummed Santa Marias beside me, our hands clasped firmly on the bed's quilt, I'd slouch my posture and begin counting the stars on La Virgen's cloak, eager for the moment my abuela would relieve me of our post.

Little did I know I chose one form of prayer for another. To lose my attention in La Virgen's image became its own act of devotion; to return her gaze an act of prayer.

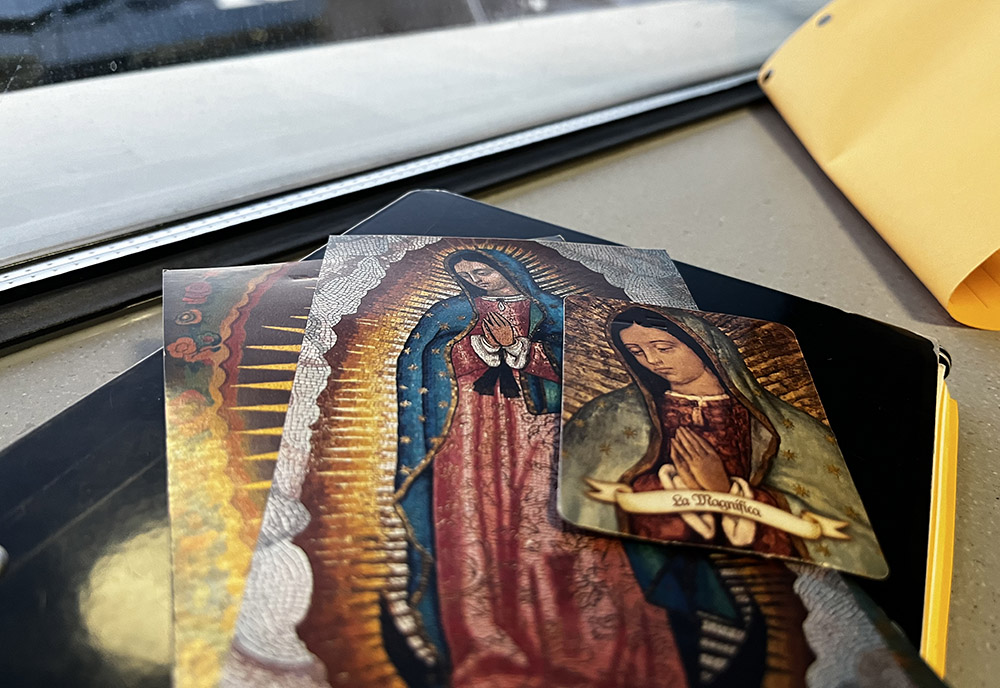

Back in Chicago, she was yet another export of a Mexican family immigrating to the United States. Virgen de Guadalupe prayer cards would suddenly appear in places least expected throughout our home: creased into hand-me-down wallets, glove compartments, between the pages of an old cooking magazine. One day, I found her tucked beneath a sandwich in my lunch box. "Para que te ayude durante el examen," my mom's note said.

At every corner, La Virgen de Guadalupe reminded us of her promised protection now and at the hour of our death. Today, I carry a stack of prayer cards in the pockets of my coat to give to Spanish-speaking patients I meet at the hospital.

Advertisement

One day, a patient asked for two prayer cards. "One to give to the surgeon, just in case," he grinned.

On another night, I met a family of nine tucked into the hospital room of their deceased mother, her hands cradling the prayer card of La Virgen as her adult children prayed and sang over her body, a single nurse hovering between them with a box of Kleenex. The tenderness of their voices invited me to sing and cry with them.

When my own abuela finally died in the middle of this pandemic, my family boarded a plane for Mexico City.

For many months, she had lain in the bedroom where she taught me to pray. In this room, her body became more bones than body and her breath softer and quieter than the flutter of a butterfly.

I did not cry at her funeral nor sang when we visited the Basilica of La Virgen de Guadalupe in her honor. Instead, I found myself wondering what photograph of her would best honor her life on my Día de Muertos altar. "Too soon," I thought to myself.

In the Basilica of La Virgen de Guadalupe, Mexico City (Steven Salido Fisher)

All around me at the basilica, other pilgrims orbited the Virgin's portrait in constant procession. Gifts of flowers and candles and prayers and songs were brought and prepared, set at the floor. It is here that women and men inch their way inside on their knees and teach their children to give thanks, as my abuela once taught me. A cyclical universe of recitations revolved across each rosary bead with a pulse that whispered, "Dios te salve, Maria." I have to start it in English to catch the words in Spanish. "Santa Maria, Madre de Dios ..."

Our return flight to the United States inevitably led to a long line at customs. A family behind me complained loudly that their vacation in Cancun was too short, and by the time I reached the front of the line, the customs officer asked me the reason for my trip, to which I could only respond with one word: "Family."

When the taxi finally returned me to my apartment, I opened my suitcase and saw all that I inherited from my abuela. I picked up her blouse and buried my face in its embroidered flowers. Her imperfectly described smell of Chapstick and frankincense and orange peels blossomed into the air, and it's like I'm back at her bedside praying to La Virgen with her, counting the stars on La Virgen's own cloak. This scent I realize will soon be lost forever, and finally I begin to cry.

My abuela told me La Virgen is always watching us from the sky to protect us. But I cannot tell you why some stars begin to fade and vanish from the night completely. I cannot tell you why a star that has burned for millennia all of a sudden sinks into the weight of its own gravity and no longer pierces our light-polluted sky.

But I do know that a prayer card can only weigh as little as .16 ounces. I take one of La Virgen from my pocket in the hospital and, fumbling my phone case open, I slip it inside to carry with me daily. It is in an act of daily remembrance and burden and prayer for others I hope to be capable of and never forget.

"Protect me," I ask La Virgen and I place my phone back in my coat pocket.