Seminarians from the Pontifical North American College walk in procession during the ordination of new deacons in St. Peter's Basilica at the Vatican in September. (CNS/Paul Haring)

The 2021 Survey of American Catholic Priests (SACP) was released this week by researchers at the University of Texas at Austin and Baylor University. It features 1,036 priests who answered 54 questions, some drawn from the 2002 L.A. Times survey of Catholic priests, to permit comparisons over time. And the authors looked at other surveys of priests, all the way back to Andrew Greeley's 1970 survey, and consulted other studies in related fields such as moral psychology.

While all of us have discovered new reasons to be skeptical of survey data after the last two elections, this survey seems to track with anecdotal perceptions from bishops and priests in recent years.

The finding that has garnered the most attention is that younger clergy tend to be more conservative than their elders on a host of issues. "We find strong empirical confirmation of the nearly ubiquitous perception that younger priests are more orthodox in their beliefs than older priests," the authors state in the abstract. "Additionally, we find a significant turn toward pessimism regarding the current state and trajectory of the Church."

I object to the use of the adjective "orthodox" here, but there is little doubt younger clergy are more conservative on moral and political issues.

Advertisement

So, for example, among priests ordained in the 1970s, 56% said that abortion is "always a sin" compared to 89.5% of priests ordained since 2010 who concur with that statement. Interestingly, those priests ordained in the 1970s reported in the 2002 L.A. Times survey that 69.7% agreed with the belief that abortion is always a sin, and the authors do not explain the discrepancy with their findings now. I am at a loss to imagine what might account for it.

One of the reasons I dislike surveys is that they pose questions that admit a variety of interpretations. So, for example, the survey report states:

Respondents were asked the degree to which they agree or disagree with this statement: "The sole path to salvation is through faith in Jesus Christ."

Obviously, at one level, this is bedrock Christian doctrine, set forth explicitly in the Scriptures and confirmed by ecumenical councils and papal teaching through the centuries. But what does it mean to have "faith in Jesus Christ"? Given that another bedrock belief is that Christ's mission of salvation is universal in scope, how is this "sole path" made available to those who have never heard of Jesus Christ? And, seeing as the writings of St. Paul are at the heart of these questions, what does St. Paul mean by salvation anyway?

Setting those quibbles aside, it is remarkable, if not entirely surprising, that the percentage of priests who strongly agree or strongly disagree with the statement about the exclusivity of salvation through faith in Jesus Christ correlates with their political self-identification as conservative or liberal. Eighty-two percent of priests who self-identify as "very conservative" politically agreed strongly with the statement, while only 19% of those who self-identify as "very liberal" do so. Similarly, 39% of "very liberal" priests disagreed strongly with the statement, while next to zero of "very conservative" priests disagreed with it.

I wonder if the GOP platform will include an endorsement of faith in Jesus Christ as the sole path to salvation! And would Donald Trump take offense?

In seeking an explanation for this correlation, the authors look to moral psychology and conclude that "conservatives and liberals, it turns out, are attuned to quite different sets of moral intuitions. For liberal-progressives, there is a strong emphasis on care, fairness, and openness, while conservatives place relatively greater emphasis on in-group loyalty, authority, order, and sanctity/purity."

They cite Jonathon Haidt's influential book The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion. If only we could all convince each other that the liberal heart and the conservative heart both yield wisdom and we should strive to master those qualities of moral psychology that belong to the kind of heart we were not born with!

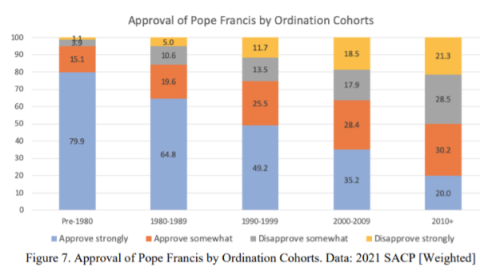

The reason to object to the adjective "orthodox" rather than "conservative" in describing the attitudes of younger clergy comes when the survey asks about Pope Francis. Overall, 53.4% strongly approve of the job Pope Francis is doing and another 22.8% approve "somewhat." But the authors state:

Among priests who describe their politics as "very conservative" for instance, 68.9 percent disapprove of Pope Francis, whether "somewhat" or "strongly." On the other end of the spectrum, remarkably, not a single priest in our dataset who describes himself as liberal on politics (whether "somewhat" or "very") disapproves of the job Pope Francis is doing (whether "somewhat" or "strongly").

When you recognize that there is also a correlation between younger clergy and being more conservative, than you realize seminary professors need to start teaching their charges that the old joke about being more Catholic than the pope was just that: an old joke.

Substantively, the correlation between being conservative on moral and/or political issues and disliking Pope Francis was clear early in the pontificate, especially during the twin synods on the family. The problem is not, as some conservatives suggest, that the pope is lax about morals. Pope Francis understood that moralism had made the church lose sight of the actual kerygma of the Gospel.

"At times we find it hard to make room for God's unconditional love in our pastoral activity," Francis wrote in Amoris Laetitia. “We put so many conditions on mercy that we empty it of its concrete meaning and real significance. That is the worst way of watering down the Gospel.” (#311)

How different would our church be if the bishops had spent the last year wrestling with the implications of those sentences from Amoris Laetitia for seminary education, rather than trying to find a way to deny Communion to Joe Biden? I hope someone asks that question next week in one of the two executive sessions the U.S. bishops are having.

Other parts of the study are reassuring. A clear majority of priests, 62%, continue to report that they are very satisfied with life, although that number is down 10 points from the 2002 L.A. Times survey. Conversely, 91.6% say they are "very unlikely" to resign the priesthood, a number that is up from the 2002 survey. The apparent divergence is likely related to the increased pessimism about the state of the church among the clergy, with 51.3% saying it is "not so good," a sentiment shared by only 33.9% of clergy in the 2002 survey.

Seminary professors need to start teaching their charges that the old joke about being more Catholic than the pope was just that: an old joke.

Additionally, 47.7% indicate they think the situation of the church is getting worse, compared to only 28.3% who thought that in 2002. Only 16.1% of clergy today think the situation of the church is getting better. Those are the priests who have taken 1 Peter 3:15 – "Always be prepared to give an account of the hope that is within you" - to heart! Assuredly, years of clergy sex abuse scandals have taken their toll on those answering these questions as well.

The principal takeaway from this survey is that bishops need to really find out what is going on in their seminaries and make sure that there is a serious attempt to "integrate the magisterium of Pope Francis," as one bishop says, into the education of future clergy. The bishops' conference needs to think of ways its work, such as setting its strategic goals, reflect such integration as well.

Unfortunately, while only a fifth of bishops may be hostile to the Holy Father, a larger percentage still think of this pontificate as a bit of bad weather that will pass.

The problem with that view, ultimately, is that it requires a distortion of the two previous pontificates also. Whatever else Popes John Paul II and Benedict XVI did or did not do, they did not reduce the faith to moralism. That was done for them by their American admirers, both men in the hierarchy like Archbishop Charles Chaput and writers in the commentariat like George Weigel and the late Fr. Richard John Neuhaus.

The bishops, in short, have their work cut out for them. Sad thing is that the leadership of the conference doesn’t seem to even recognize that need.