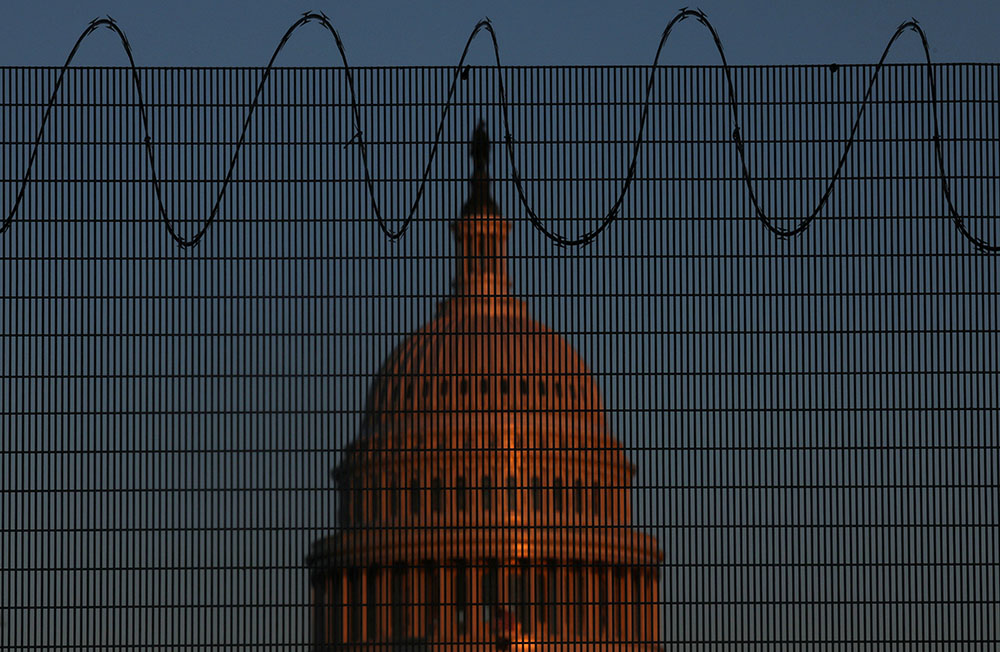

The U.S. Capitol is seen in Washington Jan. 28 behind steel fencing topped with razor wire. (CNS/Reuters/Leah Millis)

I was arrested at the U.S. Capitol.

Not on January 6, 2021, but 50 years ago on May 4, 1971.

Back then, I was part of a protest against the war in Vietnam. More than 12,000 people were arrested that day in Washington, D.C. My protest was a classic case of civil disobedience. It was ethically different from the acts of terror and insurrection at the Capitol last month. Both actions took place in the same building. There the similarity ends.

I was arrested in the Senate gallery in 1971, along with one of my roommates from the University of Virginia. We entered the gallery legally and peacefully, on passes obtained from the office of Sen. Harry Flood Byrd Jr., the "political boss" of Virginia at the time.

Our only weapon was our words. My roommate read from an essay by linguist Noam Chomsky. I read from the Beatitudes from St. Matthew's Gospel. We had transcribed them on notebook paper. Shortly after the Senate session began, we stood, one at a time, and read from the papers. My hands trembled terribly.

I remember that the senators looked up momentarily and paused their discussion. Capitol Police took a little while to reach us in the gallery. I managed to get to verse nine of the Beatitudes, ("Blessed are the peacemakers …") when four policemen grabbed me. My roommate was similarly arrested moments later.

We were immediately handcuffed and taken to a holding room in the basement of the Capitol. There we were searched, read our rights, booked, photographed and fingerprinted. Eventually, we were taken to the D.C. central lockup, which was overflowing with thousands of demonstrators arrested elsewhere around the city. My roommate and I were put into a holding cell so crowded everyone had to stand for several hours.

We were allowed one phone call. I called a number I had been given to arrange a volunteer lawyer. We hit the jackpot. Our case was assigned to Arnold and Porter, then the fanciest law firm in Washington. Before 9 p.m. our lawyer got us released on our recognizance. We took a late-night bus back to Charlottesville.

Eventually, we were convicted of a misdemeanor, "obstruction of Congress." We accepted our punishment as part of our witness. Our trial was a few months after our arrest. Before a judge in the U.S. District Court, we pleaded nolo contendere, which means we did not contest the facts, but wanted the prosecutor to prove the elements of a crime. It also gave us a chance to address the court about the reasons for our civil disobedience. The judge was sympathetic to our goals and our witness, but he correctly convicted us, because we had broken the law. He sentenced us to two years of probation.

Advertisement

The arrest came up twice later in my life.

Ten years after our arrest at the Capitol, I applied to become a lawyer in Maryland and the District of Columbia after I had passed the bar exam in each jurisdiction. I had to explain myself to a panel of judges. They found no cause to refuse my law license.

The second time was when I applied to the seminary in 1982. Cardinal James Hickey interviewed me. He seemed intrigued by my record and said, "I was going to ask you to read from the Beatitudes, but I see you already read them to the U.S. Senate."

Nonviolent civil disobedience has played an important role in social movements both in U.S. history and in Catholic social action. The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and Mahatma Gandhi outlined the requirements for ethical violation of the law, which they called civil disobedience. I can remember four elements.

First, civil disobedience must be used only in the interest of achieving a moral good or in opposing a grave moral evil, such as racial segregation or unjust wars. At its core, there must be moral "truth" in any act of civil disobedience. Gandhi called this "Satyagraha," or "truth force." Civil disobedience is not lawlessness. It takes the law seriously and recognizes that breaking the law is action to be taken only for grave reasons. The riot by Trump supporters at the Capitol on Jan. 6 was not based on truth, but based on a lie that the election was stolen.

Second, civil disobedience must be nonviolent. The riot at the Capitol in January was violent. In 1971, no person or property was physically threatened by my action. In January, five people died at the Capitol, including a police officer. Rioters threatened innocent people. They called for the lynching of Vice President Mike Pence and the kidnapping of House Speaker Nancy Pelosi.

Third, those who commit nonviolent civil disobedience must be willing to submit to the punishment of the law as part of their witness on behalf of their cause. The rioters at the Capitol tried to escape justice and evade the law.

Fourth, the protest must be "intelligible" to observers. An objective observer must be able to see the connection between the action taken and the remedy sought. The rioters at the Capitol had no clear program or purpose other than to cause chaos and stop a lawful process.

Civil disobedience has held an important place in Catholic social movements. People like Dorothy Day, Cesar Chavez and Catholics who participated in the labor and civil rights movements all used civil disobedience to try to bring about greater justice and the common good.

As the impeachment trial progresses, remember the distinction between civil disobedience and a riot. One had a moral foundation. The other was simply an act of violence.