Boys ride their bikes past boarded-up and abandoned rowhouses in Baltimore in May 2019. (CNS/Reuters/Stephanie Keith)

Racial bias has long found a home in real estate, barely disguised by a host of other motives. We move for many explicit reasons but only rarely admit the skin-color incentive. Because it can easily hide in other causes, the risks of being labeled a racist are minimal. It's just the way everybody finds a good home, we say.

No factor looms larger in perpetuating racism than this one — often blurred, however, because it is so commonly covert, overridden by issues so close to the hearts of such a vital need for shelter.

It has ridden a train of bigoted practices that keep it so even as they have been largely hidden: housing covenants, redlining, predatory lending and ongoing gentrification that often pretends to foster wholesome community growth.

The pattern continues to exist as a survival strategy for privileged white people who mainly steer clear of overt racism.

White America has openly or not cited specific worries: the loss of property values, fears of school integration, and aversion to living next to people they judge inferior. Over time, young generations have been generally found to be more accepting and tolerant of diversity, espousing racial justice ideals but bearing the largely unconscious legacy of their white privileged upbringing.

For years, I taught college students from such backgrounds who were sensitive to racial injustice while knowing little to nothing of its victims or causes. The consequences of their own ghettoization would require prolonged exposure to overcome in order to fully embrace the justice cause.

Conversely, many of their grandparents had followed the trail of white flight that had blatantly emptied scores of New York City neighborhoods and parishes for the racial purity of the suburbs.

As civil rights action began uprooting some housing discrimination after World War II, white home owners fled in alarm at the first signs that non-whites were moving in. They hightailed it mostly to New Jersey and Long Island suburbs.

Notable beacons of refuge — hailed at the time as a major symbol of America's promise — were the Levittown sprawling rows of efficient, affordable houses for aspiring middle-class families. Unless they were Black. Explicit exclusion kept them out.

Advertisement

So it continues, under various subterfuges. Gated communities, city coops, quiet agreements, racial steering and myriad retirement complexes.

Bias operates so smoothly. It flows from perfectly acceptable reasons for seeking adequate, safe surroundings where individuals and families can "feel at home."

In a groundbreaking 2009 book titled The Big Sort, authors Bill Bishop and Robert B. Cushing exhaustively documented how preferential bunching had produced the most extreme economic and racial separation since the Civil War.

The rush to move to places of similar income, politics and race had gained enormous force, they showed, with the result that America had become self-segregated into tight enclaves of likeness. Though their main focus of this bowdlerization was its polarizing effect in politics, the accompanying racial divisions were crystal clear.

Mixed neighborhoods were becoming things of the past. "Everyone can choose the neighborhood (and churches and news shows) most compatible with his or her lifestyle and beliefs," they wrote. Moreover, these demographic islands "have become so ideologically inbred that we don't know, can't understand, and can barely conceive of 'those people' who live just a few miles away."

They summed up the impact of this clustering this way: "Mixed company moderates; like-minded company polarizes."

Racial superiority and stereotyping ordinarily go largely unchallenged and routinely in the housing market. Franciscan Fr. Richard Rohr, a widely respected spiritual mentor, recently wrote that "evil can hide in systems much more readily than in individuals." While he wasn't alluding specifically to the harboring of housing injustice, Rohr's words offer insight into how racism flies under the radar.

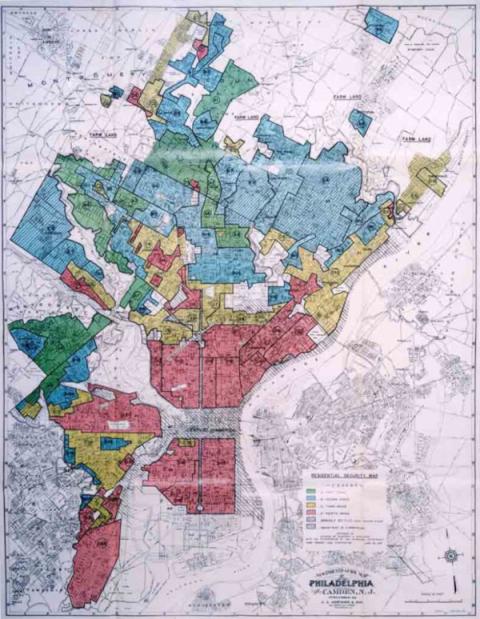

HOLC security map of Philadelphia showing redlining of minority neighborhoods. (United States Federal Government)

An influential voice from the Ford Foundation relates that scourge to housing bias. Xavier de Souza Briggs (no relation) spearheads Ford's top priority of fighting inequality across class and racial lines. He is a former MIT scholar who has worked on related issues in the Obama and Clinton administrations.

Interviewed in 2018 by the Inside Philanthropy periodical, he laid down the major premise of Ford's ambitious initiative, noting that while the nation's cities have changed much over the past 50 years, "entrenched poverty remains a constant. And housing segregation, along with the legacy of redlining, ensures that it often follows racial lines."

Deliberate efforts to create high-priced zones crowd out the poor and further inequality, he adds, whereby "the legacy of intentional segregation shapes opportunity [for racial and economic disparities] even as redlining and discriminatory covenants fade into history." He points to the dearth of affordable housing as a devastating outcome to zoning manipulation, meaning "that nothing affordable to people of low or moderate income can be built at all in your area."

Combating racism covers a wide array of aims, of course, but the huge damage from its housing bias rates highest priority along with schooling and work. A starting point is a consciousness-raising effort to encourage personal examination of racial attitudes in this regard, particularly hidden persuaders that steer us in harmful directions.

I had a personal brush with this dilemma recently when selling my house in Pennsylvania. It's a lovely two-story late Victorian on a picturesque block that has been modestly priced and highly mixed — Black, white, Hispanic, family, single, straight, gay. Over the past five years, the city had gone berserk with gentrification in the name of city revival. The house was downtown, ripe for "upgrading."

My plan was to sell it to local people of modest means, with hopes for a minority buyer. That effort failed. Developers and financers from the New York area have swooped in to grab up properties at bargain prices (in their scheme of things), fix them up and rent them or sell them way above prevailing rates. And they pay cash.

Somehow, I believed I could beat that system. But the first week on the market, only big city agents showed up. Apparently, the wider neighborhood had gotten the message that this block was no longer for them. I gave in, bitterly disappointed, feeling as if I'd got rolled. The house was refurbished to museum quality. The rental for it is three times what my mortgage used to be.

[Ken Briggs has reported on religion for Newsday and The New York Times, contributed articles to a variety of publications, written five books and taught for 18 years as an adjunct professor at Lehigh University and Lafayette College. He lives in Indiana and continues to be a freelance writer.]

Editor's note: You can sign up to receive an email every time Roundtable is posted. Sign up here.