A young Rwandan stares at bodies in a mass grave July 20, 1994. (CNS/Reuters/Corinne Dufka)

In the 1994 Rwandan genocide, at least 800,000 people, mostly from the Tutsi ethnic group, were slaughtered in 100 days. It was another among countless examples of the evils that colonialism brought to the African continent and elsewhere.

Belgium came to rule that east-central African land in 1916 and, decades later, left it ripe for exactly the kind of irrational murderous rage that took place in that largely Catholic country, a rage described in deeply personal ways in this new book.

As the BBC recounted in a retrospective 2011 story about how the genocide happened, the colonial rulers of Rwanda, early in their reign, "produced identity cards classifying people according to their ethnicity. The Belgians considered the Tutsis to be superior to the Hutus. Not surprisingly, the Tutsis welcomed this idea."

Jean Bosco Rutagengwa, the Tutsi survivor who wrote this book, puts it this way: The Belgians "developed theories that Tutsi, who were cow herders for the most part, were more intelligent and more refined than their fellow compatriots, the Hutu, who were farmers. … The Belgian colonials even went as far as measuring Rwandans' noses and other physical dimensions, asserting that Tutsi were taller and had longer and narrower noses."

(Late in their rule, the fickle Belgians began to favor the Hutus, who gained the upper hand and killed thousands of Tutsis or drove tens of thousands of them into exile before Rwanda became independent in the early 1960s.)

Belgian rule was incoherent racial identity politics at its worst. From that racism, the precise lines of the genocide story might not have been predictable, but they weren't surprising.

Hutus and minority Tutsis battled for supremacy until the airplane of the president (a Hutu) was shot down in April 1994, causing Rwandans to erupt into lethal bedlam as hardline Hutus took revenge on the Tutsis and some moderate Hutus for that killing.

Advertisement

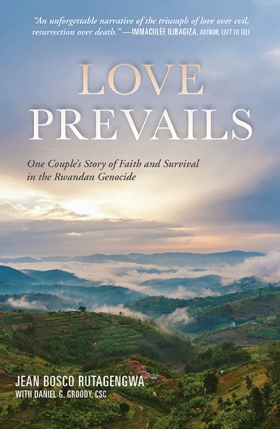

What Rutagengwa tells here is the remarkable story of how he and his fiancée (now wife, Christine) stayed alive (barely) and how Rutagengwa almost abandoned his Catholic faith amid the unfathomable blood and gore that destroyed most of their families. But it's also the story of how he finally recovered that faith.

It's a harrowing tale that — despite some occasional overwriting and reliance on clichés — is quite well told, especially now that enough time has passed to let the author, who moved his family to the U.S. in 2000, process his experiences.

When genocide broke out, the author notes, many Rwandans "did not think that evil could prevail over the forces of good. After all, Rwanda was a majority Christian nation, with an impressive church presence."

The shock to Rutagengwa and others was that supposedly good Catholics could murder one another with abandon and that both Hutus and Tutsis could commit such atrocities, a reality made clear by the behavior of current Rwandan President Paul Kagame, a Tutsi. He is given credit for stopping the genocide, but as Harper's Magazine recently reported, Kagame has been "brutal from the beginning," his reign "marked by widespread human-rights abuses, likely including the assassination of political opponents."

The many near-death experiences suffered by Rutagengwa and his fiancée — including their stay in what later became famously known in a film as "Hotel Rwanda" — are the stuff of thriller movies. Somehow, he writes, luck, courage, prayer and inexplicable circumstance combined to keep them alive when their deaths often seemed minutes away.

Rosaries are seen near skulls of victims of the Rwandan genocide on display at the Genocide Memorial in Kigali April 6. Rwandans are marking 25 years since a genocide in 1994 that killed hundreds of thousands of people. (CNS/Reuters/Baz Ratner)

Over and over, Rutagengwa must confront the reality that Christians — mostly Catholics — brutalized one another: "Was this the Rwanda I grew up in? What had happened to humanity?"

Eventually he decided there was no point to life or faith: "I lost the capacity for hope." His question was: "How does one live with the enormity of evil and remain a sane human being?"

It's a question we all confront if we're paying attention. Rutagengwa's answers may not, in the end, be our own, but his experience can guide us toward a life rooted in eternal values even if we're trying to survive hell on earth.

[Bill Tammeus writes the daily "Faith Matters" blog for The Kansas City Star's website, a column for The Presbyterian Outlook and a column for Flatland, KCPT-TV's digital magazine. His latest book is The Value of Doubt: Why Unanswered Questions, Not Unquestioned Answers, Build Faith.]